By Jordan Levinson

When we see most musicals, they tend to use spoken word and song to get their point across, with elements of dance mixed in. However, there have also been several “dance revues” through the years in which the choreography does the heavy lifting. For instance, earlier this week, MCC Theater’s Only Gold officially opened. It tells the story of a royal family returning to Paris in the 1920s (including a king who tries to save his fading marriage) and three couples falling in and out of love, making everyone in town reexamine their lives and the choices they have made. Using the music of singer-songwriter Kate Nash, the diverse, multitalented cast performs Andy Blankenbuehler’s choreography, a series of moves that turn “eye-catching sequences into long narrative arcs.” (The New York Times) Their postures, twists, and turns tell the bulk of the story.

Meanwhile, it was recently announced that a revival of Bob Fosse’s Dancin’ will arrive on Broadway in the spring; previews begin March 2 at the Music Box Theatre with an official opening set for March 19. A tribute to the art form that is dance, Dancin’ sets Fosse’s moves to a variety of musical styles and artists — from Mozart and Bach to Cat Stevens and Neil Diamond and everything in between — celebrating his influential form and exemplary spirit. The revue was nominated for seven Tony Awards, winning two (including Fosse for Choreography), and running on Broadway for over four years and 1,774 performances.

Other “dance-icals” have jetéd to NYC in seasons past, to varying degrees of success. The late 1990s and early 2000s especially saw a renaissance of extended dance pieces reach New York stages.

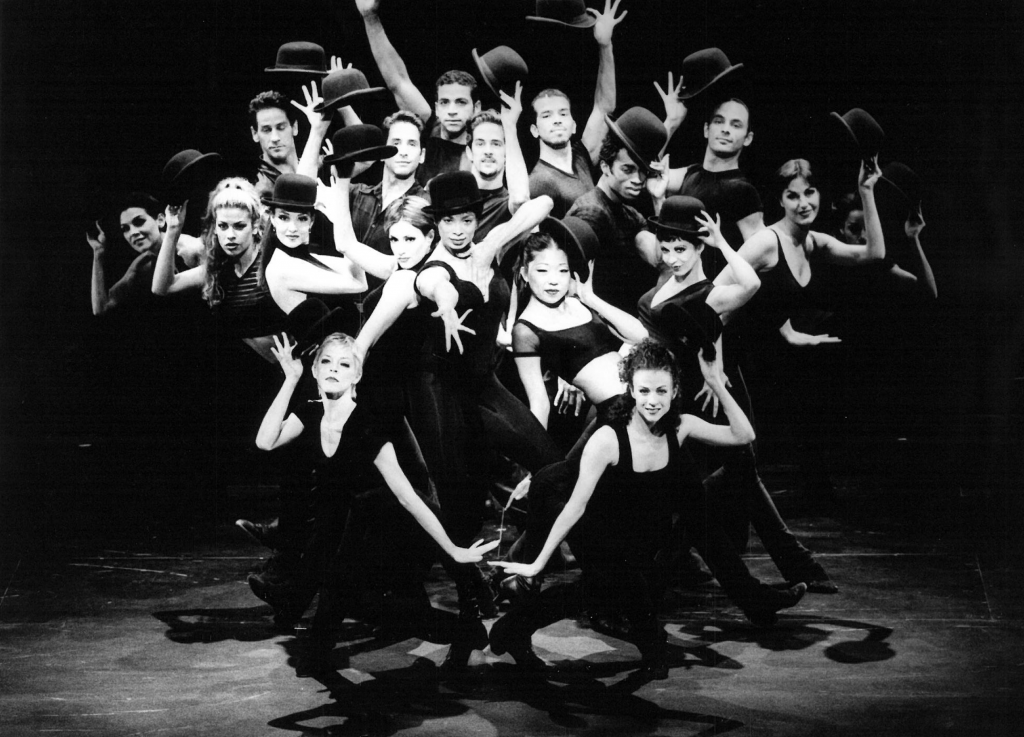

The three-act musical revue Fosse is a more direct link to the many shows Bob Fosse worked on, and some of their most memorable numbers. Conceived by Fosse interpreter Chet Walker, Fosse played over 1,000 performances at the Broadhurst Theatre, from 1999 to 2001.

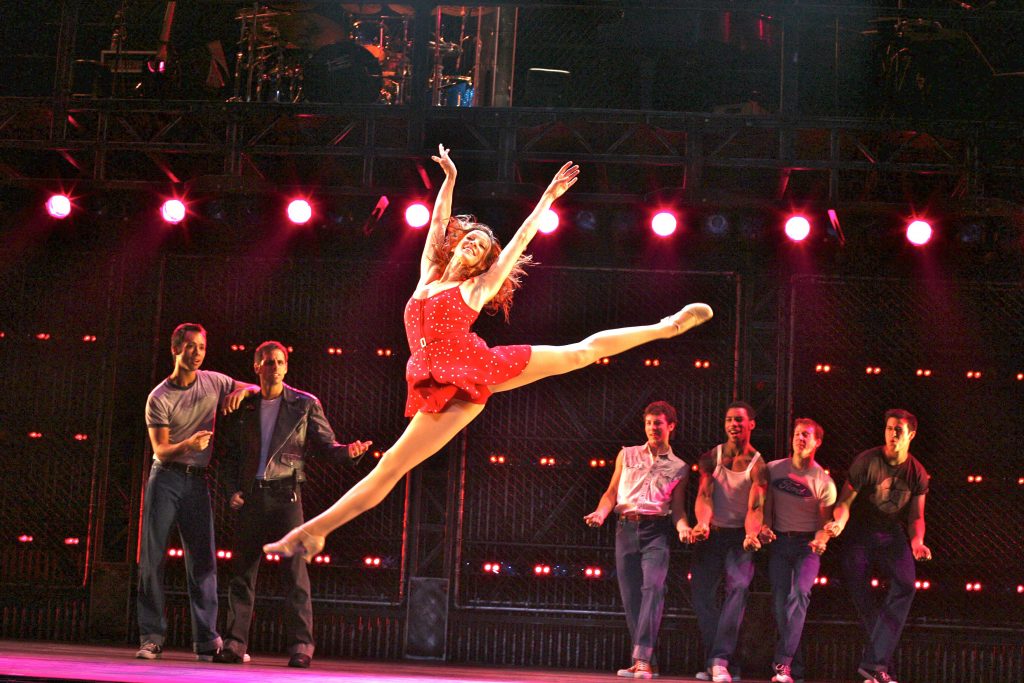

Lincoln Center Theater also got in on the dancing act at the turn of the century, as Susan Stroman’s Contact opened in March 2000 and was met with critical acclaim. Made up of three separate extended dance pieces (and set to prerecorded music from all different eras, from Tchaikovsky to The Beach Boys), each one follows a central character’s desire to make a romantic connection or increase their “contact.” Contact won four Tonys including Best Musical but did not shy away from controversy because there was no live singing or original music in the show; a separate award for Best Special Theatrical event (which has since been discontinued) was introduced the following year.

In 1996, Savion Glover (of next season’s Pal Joey revival) put on his dancing feet as he choreographed Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk, which also won four Tonys (including Choreography). Here, dance served as both entertainment and a guide to history, as the concept of this revue revolved around the Black experience, from slavery to the present day. Glover was also part of the dynamic original cast, returning to the show for its final weeks before it shuttered after a successful 1135 performances.

Right before the dawn of the 2000s, Lynne Taylor-Corbett’s swing musical, the aptly titled Swing!, opened December 1999 at the St. James Theatre. Told entirely through music and dance, the show celebrates the look and sound of the swing era; Swing! featured well-known tunes from Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and many others. Though it didn’t win any Tonys, it was nominated for Best Musical and Choreography; it closed after over a year on Broadway.

Even the Irish received some love in New York at the turn of the century, as a company of 16 led Riverdance to the Great Bright Way. This show’s path was an unorthodox one, having been an interval act during the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest. It was expanded into a stage show the following year, opening (where else?) in Dublin. To this day, over 25 million people have witnessed the step-dancing wonder of Riverdance, in over 450 venues worldwide. It ran for a year and a half in New York, from early 2000 to mid-2001.

The early 2000s introduced the world to the work of renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp, who had three separate Broadway “dance-icals” utilizing the work of popular artists. The most successful of them was Billy Joel’s Movin’ Out, about a group of Long Island youths and their experiences with the Vietnam War. The rock ballet ran three years (2002 to 2005), won two Tonys (Joel for co-orchestrating, as well as Tharp), and spawned a national tour — a commercial hit.

Tharp also received a Tony nomination for her short-lived 2011 Frank Sinatra ballet Come Fly Away, which, like that of Contact, told the story of several couples in search of love. Despite only lasting five months on Broadway, it also received a national tour of its own.

A valid reason as to why all these moving-and-grooving productions have popped up here and there is that dance is a language of its own. When words can’t say quite enough, choreography at its finest can be expressed by emotion and physical expression. Dancing breaks all language barriers and can easily be communicated amongst vastly different cultures. “Dance-icals” get their point across to both English and non-English speakers, opening themselves up to large audiences whenever they kick-ball-change their way over to Broadway houses.