By Linda Armstrong

There is something so moving when a drama, and a One Act that was delivered through only three characters (Cephus Miles, Pattie Mae and Woman Two)—portraying over 25 roles–can grip the audience and discuss such relevant, socially significant topics.

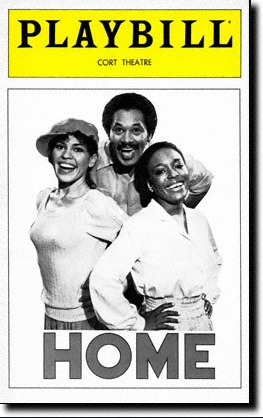

It is absolutely marvelous, the contributions that the Negro Ensemble Company (NEC) has made to Broadway Theatre through the decades. It has proven to be a vessel through which creative, black writers have gotten to get their voices heard and appreciated. In the 70’s “The First Breeze Of Summer” by Leslie Earl Lee originated there and moved to Broadway. In the 1980s, Samm Arthur Williams {Samm Art-Williams} play “Home” followed suit. It was first performed at the Negro Ensemble Company and then previewed on Broadway at the Cort Theatre April 29, 1980, opening May 7 and closing January 4, 1981. During that time it was nominated for two Tony Awards and two Drama Awards for Best Play and Outstanding Actor in a play, Charles Brown. The play won the Outer Critics Circle Award for John Gassner Playwrighting Award in 1980 and the Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts, U.S. & Canada in 1981.

Art-William’s not only looks at the Black experience in “Home”, he also takes on the serious topic of the Vietnam War and how some Black men chose to be conscientious observers and not fight, even if it meant prison time. One realizes that the draft was a system that the government used to get poor Blacks into the military and it was simply unfair on so many levels. There is something so moving when a drama, and a One Act that was delivered through only three characters (Cephus Miles, Pattie Mae and Woman Two)—portraying over 25 roles–can grip the audience and discuss such relevant, socially significant topics. Topics that are still relevant 41 years later, with how some people still feel about fighting in Wars and the injustices that happen to Blacks in this country. In Art-Williams play “Home” originally performed at NEC and then transferred to Broadway, one experienced a drama which begins in the 1950s and goes through to the Civil Rights Movement, about a Black male–Cephus Miles–coming of age in the small community of Crossroads, North Carolina where segregation is alive and well. Miles is an orphan who was left his family’s farm. He is trying to find his way in life and love. He is also someone who serves five years in prison for being a conscientious objector pertaining to the Vietnam War in which he refused to fight. The One Act play, which took 1 hour and 45 minutes to unfold, found Cephus in love with his high school sweetheart, Pattie Mae. That relationship proved to break his heart, as she went away to college and fell in love with and married, a professional man that showed promise. When Cephus returned to Crossroads after serving the five years in prison, taxes had claimed his farm. Moving to the big city he found himself doing manual labor of loading and unloading trucks, until his prison record got him fired. He went from welfare to getting involved with street life—drugs and prostitution. He hit rock bottom and gets an invitation to come back to Crossroads, someone has bought his farm. When he returns 13 years later, the segregation that had been a part of the town is over, but the townspeople consider him an outsider and spread lies about him being mean. His world becomes improved after he learns that not only is Pattie Mae divorced, but she is the one who bought his family’s farm for them to have a life together. The two find that they left their small town looking for happiness only to return and discover the true meaning of home. “Home” looked at how we are connected as human beings and takes us through the cycles of life that we go through going from adolescence to adulthood.

When “Home” was on Broadway it remained with direction by Douglas Turner Ward. Playing 278 performances the cast consisted of Charles Brown as Cephus Miles; L. Scott Caldwell as Pattie Mae Wells and Michele Shay as Woman Two.

The timelessness of this play has been displayed in the fact that it has been revived a few times. In the Signature Theatre’s 2008-2009 season dedicated to NEC, “Home” was revived at the Peter Norton Space. It previewed Nov. 11, 2008, opened Dec. 7 and ran through Jan. 4, 2009. The cast consisted of Kevin T. Carroll, Tracey Bonner and January LaVoy. It was directed by Ron O.J. Parson. It was also presented by Rep Stage in March 2013 at Howard Community College’s Horowitz Center and featured Robert Lee Hardy, Felicia Curry and Fatima Quander, with direction by Duane Boutte.

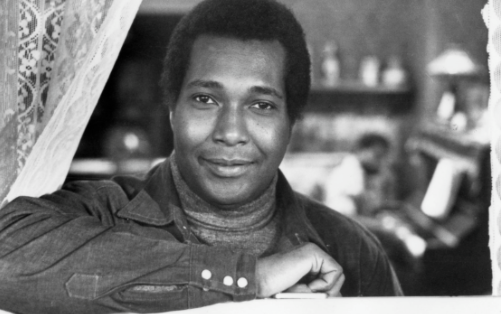

Art-Williams writing about life in the south was perfectly appropriate as he is a child of the South and lived through segregation and racism. Born January 20, 1946 in Burgaw, North Carolina, he was the son of Valdosia and Samuel Williams. His mother was a school teacher and Art-Williams attended segregated public school through high school. He was educated at Morgan State University and is an Artist in Residence at North Carolina Central University where he teaches rules of equity theatre and the art of playwrighting. Art-Williams has had a very creative life. He proved himself to be a versatile actor, as he originally performed in New York theatre in plays including “Black Jesus” in 1973, in NEC productions of “Nowhere to Run, Nowhere to Hide” in 1974 and “Liberty Calland,” “Argus and Klansman” and “Waiting for Mongo” in 1975. Taking on the role of the playwright, Art-Williams (a name change he chose to make before performing in the last two NEC plays mentioned above) wrote “Welcome to Black River,” which was produced by NEC, “The Coming,” and “Do Unto Others”, produced by the Billie Holiday Theatre in Brooklyn in 1976, “A Love Play” produced by NEC in 1976, “The Last Caravan” in 1977 and “Brass Birds Don’t Sing”, both at New York City Stage 73 in 1978. “The Sixteenth Round” in 1980, “Eyes of an American” in 1985, and “The Waiting Room” in 2007, were produced by NEC. He wrote and directed the play “The Dance on Widow’s Row” produced by New Federal Theatre in 2000. He has been executive producer of television series like “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air”. He was nominated for an Emmy Award in 1985 for Outstanding Writing in a variety or Music Program for Motown Returns to the Apollo. He was story editor for “Frank’s Place” which was nominated for an Emmy in 1988 for Outstanding Comedy Series.

“Home” may have been his only work to reach Broadway, but his plays touch the heart of any audience and completely succeed in relying the Black experience in this country.

Linda Armstrong is a theatre critic with the New York Amsterdam News and Theatre Editor for Neworldreview.net, a global online magazine.