By Mark Peikert

Everything about The Minutes on Broadway has been crafted to make its world seem as real and as familiar as a half-remembered episode of a classic Americana sitcom. A lost episode of The Andy Griffith Show where Opie learns about local politics, maybe.

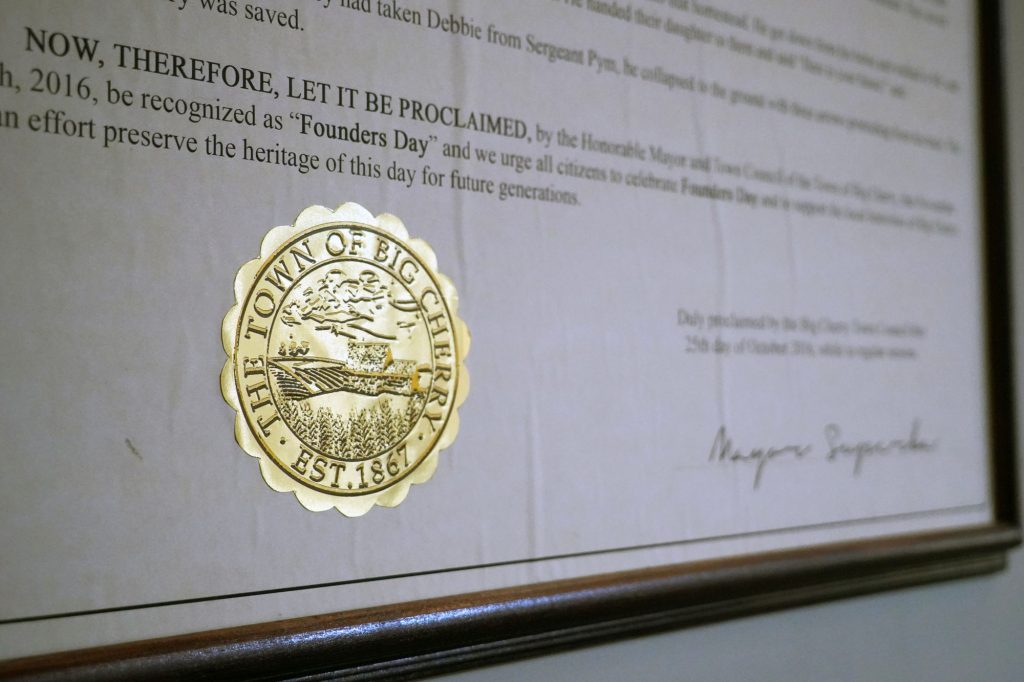

The Minutes is, however, a Tracy Letts play—so it doesn’t take very long before things begin to shift from the comedy of small-town bureaucracy to something more sinister. Told in real-time during a city council meeting, Letts’ play lures audiences into expecting something very different than is what is on the playwright’s mind. But it all begins with the set on the Cort Theatre stage, a room of desks and framed certificates and flag stands as instantly recognizable as your parents’ living room.

It’s an American iconography. You feel that immediately when you walk in the door because it’s so recognizable.

“The setting carries with it an iconography,” director Anna D. Shapiro says. “You look at the set, you see those tables, all those little microphones, you see the flags behind them—I mean, it’s an American iconography. You feel that immediately when you walk in the door because it’s so recognizable.”

That familiarity—culled by set designer David Zinn from an actual coffee table book of city council rooms—is the result of a specificity so honed that it becomes universal. “When you’re that specific, it really tightens the focus,” Shapiro says. “The audience starts to understand that contract of where they’re looking for their information. And all that we’re trying to do in theater is figure out a way to communicate the contract to the audience as fast as possible: These are the rules, these are the possibilities, this is the world.”

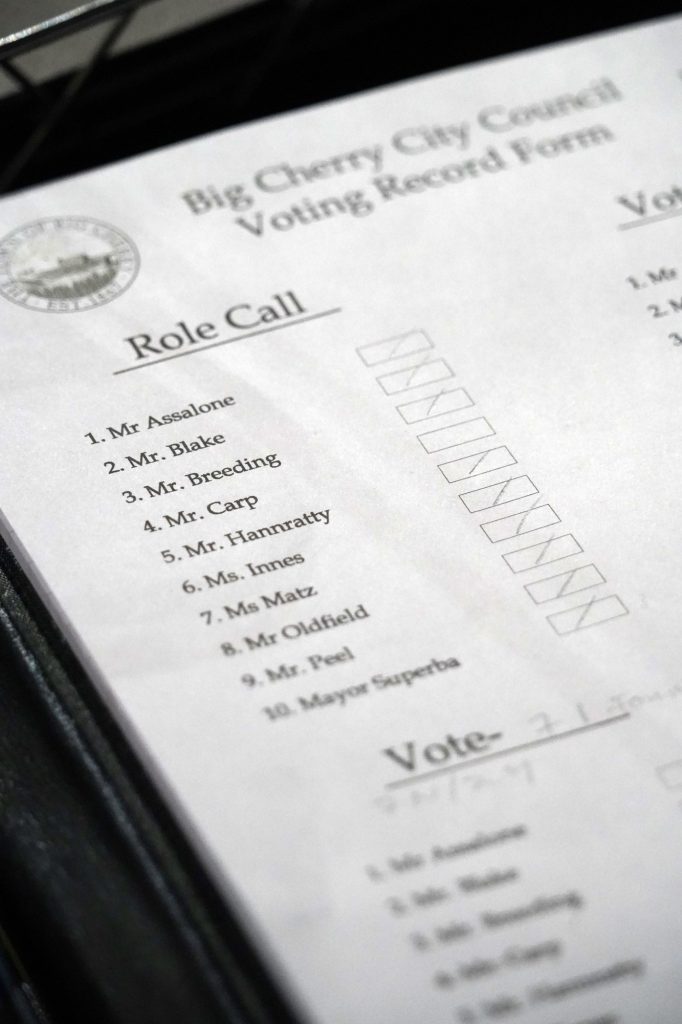

The set is all Zinn, but the individual props on each council member’s desk all came from the performers. Each character may seem like an archetype—the befuddled but vocal older man; the very prim and dignified woman of a certain age; the combative guy; the new guy still figuring it out—but each is also a fully realized person participating (or zoning out) in the meeting being held.

“I have to say, I watched probably 100 hours of YouTube videos of city council meetings from all over the country,” says Letts, who also stars as the mayor. “If you suffer from insomnia, let me recommend you watch 100 hours of YouTube videos of city council meetings, because they’re crashingly boring. But they’re also very funny in their own way.”

For a play about politics on Broadway in 2020 (and one written in 2016, no less), The Minutes is both apolitical and shockingly current. “I don’t think the words ‘Republicans’ or ‘Democrats’ are ever spoken in the play,” Letts says. The Minutes is not intended to be a comedy about political party differences; what Letts and Shapiro are interested in is engaging audiences about bigger questions. “How do we conduct ourselves as a civilization, as a society, particularly an American society?” Letts says. “And I think it’s asking some very basic questions about the kind of society you want to live in. Where do you want to live and how would you have us conduct ourselves in the world? And I hope it’s doing it in a comic and accessible way.”

Beyond local government and its politicians, Letts points out that the way we behave in any meeting—be it in an office, during a job interview, or anywhere else—is a different mode of conduct than in a restaurant or with friends. “You see a lot of different types surround the table that you recognize,” Letts says, adding that he also drew upon meetings with at the Steppenwolf Theatre for the play, “though I won’t mention any of them by name.”

“You know, you could watch it several times because you could track one person through the whole thing once you actually know the plot of the piece,” Shapiro adds. “It would be fun to be able to watch your favorite character and how they dealt with all of these little moments that you didn’t understand the first time you saw it.”

Those little moments add up to what Shapiro refers to as “a tipping point” in the play. In fact, it’s a major reason the play is 90 minutes long, with no intermission. “It takes a really long time for things to either go bad or get good, but the truth is that there is a tipping point,” Shapiro says. “There’s a moment where you go from being OK to not OK. There’s a moment where you were healthy, and then there’s a moment where you aren’t. There’s a moment where the German town became a Nazi village. There’s a moment, those things happen. And I think it’s important to know that that can happen in minutes.”