Nostalgia has always been a powerful force in the theater – and right now, it’s stronger than ever.

With shows on Broadway and around the country unlikely to resume until the current pandemic’s final phases of reopening, fans and professionals alike find themselves missing almost everything about going to the theater. The sound of a live orchestra tuning up for an overture. The feeling of an audience-wide belly laugh. The hush that falls over a crowd at a dramatic moment. Pretty soon fans might start to miss the bathroom lines at intermission.

Nostalgia is evident, too, in the ad hoc streaming offerings that theater people have produced during the current lockdown. Original casts have reconvened online for readings of shows like “Significant Other,” while Seth Rudetsky’s ongoing variety show “Stars in the House” regularly hosts reunions of TV and film actors. Even playwright Richard Nelson’s just-written “What Do We Need to Talk About?” was performed over Zoom in conversation with the past, bringing together a familiar cast of actors reprising characters they’d portrayed in the four previous shows that comprise Nelson’s Apple Family Play.

“We’re all streaming content that is based in reminding us what it was like to go to the theater,” says Elizabeth Wollman, the Baruch College theater professor whose books include “The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, From ‘Hair’ to ‘Hedwig.’” “One of the reasons that I thought the new Apple Family play worked so beautifully is because it did exactly what those plays do in the theater.”

All of this is just the latest evolution of the way in which nostalgia has always had a presence theater. It’s baked into the form itself. “Theater is defined by legend, because each performance is once in a lifetime,” says Laurence Maslon, the New York University Tisch School of the Arts professor and the author of “Broadway: The American Musical.” Either you were in the house at “Gypsy” the night that Patti LuPone snatched a cell phone out of an audience member’s hand, or you weren’t.

The memory of a night at theater is more than just the show itself. It’s where you were, who you were with, what you did before and after the performance, and all the sense memories associated with those things. “It’s coming out of the subway and smelling the salty pretzels and getting a drink at Joe Allen,” Maslon says of the Broadway experience.

It’s no accident, then, that theater has always celebrated its history — its groundbreaking productions and talents — more than TV or film: The impulse rises from the effort to preserve what we can of an impermanent form, and it’s part of why we return so often to classic plays and musicals.

“People want musical art to be timeless, and it isn’t,” notes Raymond Knapp, the UCLA musicology professor whose books include “The American Musical and the Formation of National Identity.” “The impulse to revive is very, very strong. It’s partly based on nostalgia, and it’s also based on the notion that music transcends time.”

Revivals and even new works can draw on nostalgia on both a national level and a personal one. “The idea of doing a revival of ‘The King and I’ or ‘My Fair Lady,’ those tap into a national, theatrical, Broadway-musical sense of nostalgia,” notes Stacy Wolf, the Princeton University professor and author of the book “Changed for Good: A Feminist History of the Broadway Musical.” “Broadway can be nostalgic in wanting to revive classics like those that have this aura of Americana, or sometimes, like ‘Jersey Boys,’ a show can speak to individual theatergoers or generations of fans and to their personal feelings of nostalgia for the music they grew up with.”

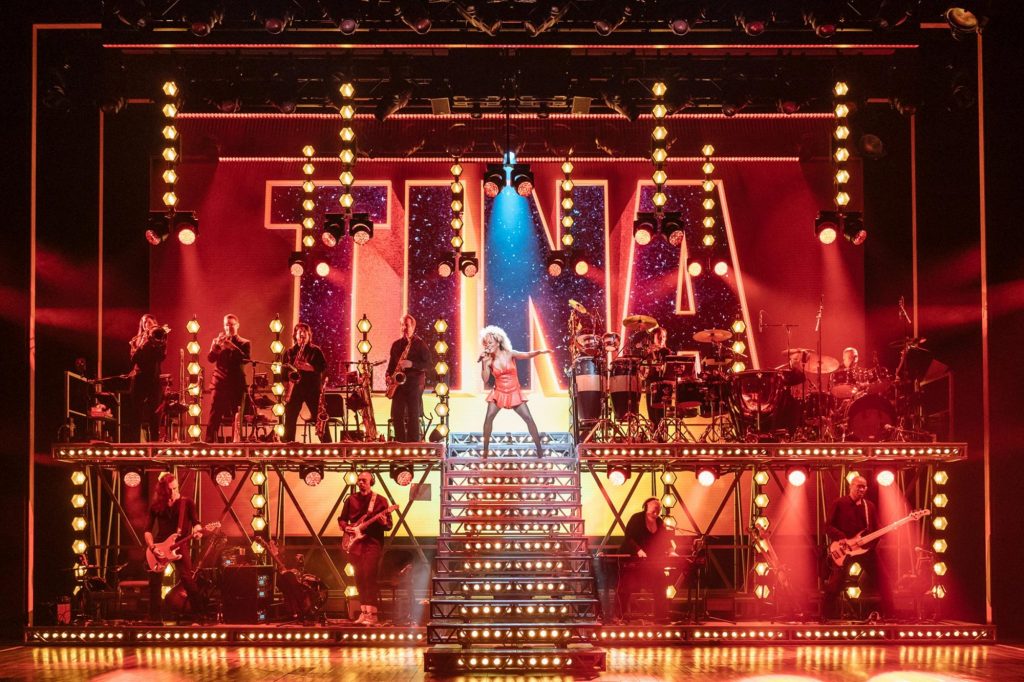

For some critics and scholars, nostalgia raises red flags. Commercial producers and nonprofit theaters alike sometimes ignore new work to return again and again to established sellers like “The Sound of Music” and “Death of a Salesman,” and many new musicals draw on popular song catalogs – The Four Seasons (“Jersey Boys”), ABBA (“Mamma Mia!”), Tina Turner (“Tina”) – rather than original scores. “I get nervous about the word nostalgia, because executives often lean too heavily on it, or it’s their own personal nostalgia that clouds their decision making,” says Ashley Lee, the theater reporter at the Los Angeles Times.

But don’t dismiss nostalgia entirely, warns Chris Jones, the longtime theater critic at the Chicago Tribune. “Nostalgia is a powerful force in why people go to the theater, and some of my most glorious moments in the theater have been really driven by nostalgia either for me or the people around me,” he explains. “I remember being at the opening night of ‘Mamma Mia!’ in London, and the audience on this wave of joy remembering their youths. Or when I was at a press performance of ‘Jersey Boys’ on Broadway where I would say, of all the tens of thousands of shows I’ve seen in my life, I don’t think I’ve ever seen an audience so excited.”

Right now, looking to the past can also provide clues to what Broadway and the theater business will look like in the coming months, when they finally reopen. Many point to the post-9/11 popularity of good-time shows like “Mamma Mia!” and “The Producers” as an indicator that in the wake of the coronavirus, audiences and producers will similarly gravitate to escapist fare.

But looking further back suggests that the future might not be all frivolity. Maslon notes that during the Depression, Broadway was a place not just for crowd-pleasing baubles like “Anything Goes” but also for socially consciousness works like “The Cradle Will Rock.” “There was this bifurcation where Broadway was either escapist or very engaged,” he says. “It actually forced theatermakers to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and to be very much in vogue and at the forefront.”

Gordon Cox is a theater journalist and the host of Variety’s Stagecraft podcast.