You might not think you can draw a line from Andrew Jackson to the sensual allure of the musical Moulin Rouge!, or that Herbert Hoover has anything to do with the anarchic fun of Broadway’s Beetlejuice. Alex Timbers, however, has proven the connection. Long before he directed those productions, he injected a similar, raucous spirit into three different musicals about American presidents.

In Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson, the 2010 Broadway show he created with Michael Friedman, he turned the Commander-in-Chief into a swaggering emo rock star. In 2015’s Here’s Hoover!, he let Hoover take the stage and argue, via rock songs, that he deserved a better reputation. And back in 2003, he directed Kyle Jarrow’s insouciant show President Harding is a Rock Star, which put a wild new slant on Teapot Dome and other scandals.

These projects not only helped Timbers develop the aesthetic style he’s carried over to his current Broadway hits, but also let him explore his particular fascination with the American presidency. The office has enticed countless theatre artists, since it offers so many angles for investigating America’s identity, history, and possible future.

Timbers is especially interested in subverting our common notion of the role. “There is something fun about taking presidents, whom one thinks of as very staid and buttoned-up, and ripping open that shirt collar,” he says. “Without being wildly rigorous with the depiction of these people, you can still capture their spirits and the way they catalyzed moments in history.”

Take the antihero of Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson: “We depict him as a frustrated teenager in the suburbs who feels overlooked by his parents, and even if that’s not literally true, it does get at something real about who Jackson was,” Timbers says. “He felt disenfranchised, and he felt that the frontiersman wasn’t being represented by the government.”

Timbers is also intrigued by the brevity of the president’s power, which only lasts a maximum of two terms. “I’ve always been interested in legacy,” Timbers says. “With kings, you die without knowing your legacy, but with presidents, you can live half your life after you’re out of office. You can see your legacy taking shape in front of you.”

It makes sense that he would compare a president and a king. According to cultural critic Isaac Butler, “If you’re doing a drama about the president, it allows you to engage in the same things that are so pleasurable about Greek tragedies or about Shakespeare’s history plays. You can tell the story of big social transformations and the nature of politics itself through the actions of one complicated individual.”

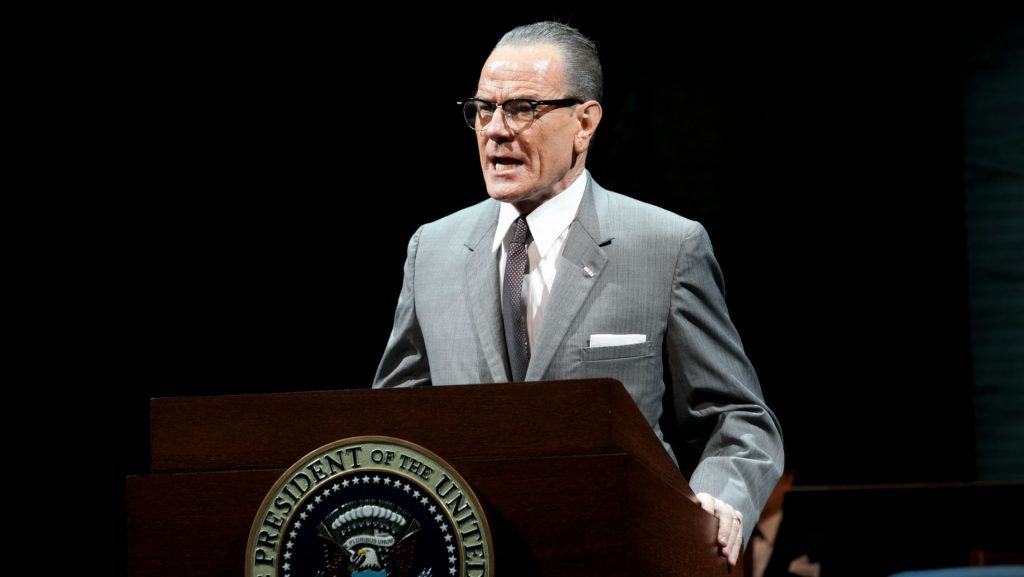

That epic sense of narrative certainly informed Robert Schenkkan, who wrote a two-play history cycle about Lyndon B. Johnson: In All the Way, which won the 2014 Tony Award for Best Play, we see Johnson on the ascendant, pushing to pass the Civil Rights Act and learning how to wield his office on behalf of his ideals. In The Great Society, which premiered on Broadway last fall, we see his plan for the titular social reform get swallowed by the quagmire of the Vietnam War.

“I was very much thinking about Shakespeare when I wrote, and the sense of the wheel of fortune rising and falling,” Schenkkan says. “There’s a rise and fall of kings, and LBJ was the king. All plays are, to varying degrees, about the acquisition, distribution, and use of power, and nothing is more clear in that regard than the narrative of how one becomes president and then how one governs as president.”

Americans deeply understand that story. No matter how long one has lived in the country, the president’s power — and that power’s ability to impact our lives — is impossible to overlook.

In fact, long before he wrote about him, Robert Schenkkan had a first-hand encounter with LBJ’s influence. The future writer was only three or four years old at the time, visiting the then-senator’s Texas ranch after his father (a major player in public broadcasting) got an invitation. And while Schenkkan doesn’t remember much about the trip, he has asked his older brother for details.

“My brother told me, ‘I don’t remember LBJ specifically, but what I remember is how incredibly respectful our father became around this strange man,'” Schenkkan says. “And what’s interesting about that to me is the child’s perception of his father’s response to the presence of power. That’s what stuck with him. I think that’s a really illuminating anecdote.”

That’s the kind of story, in fact, that could become the basis of a play.

Mark Blankenship is the founder and editor of The Flashpaper and the host of The Showtune Countdown on iHeartRadio Broadway.