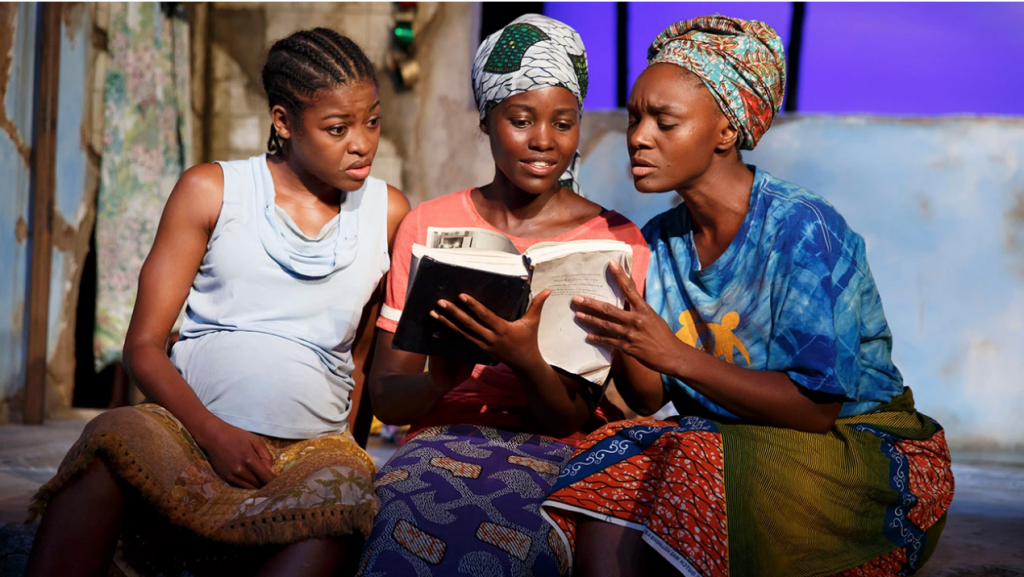

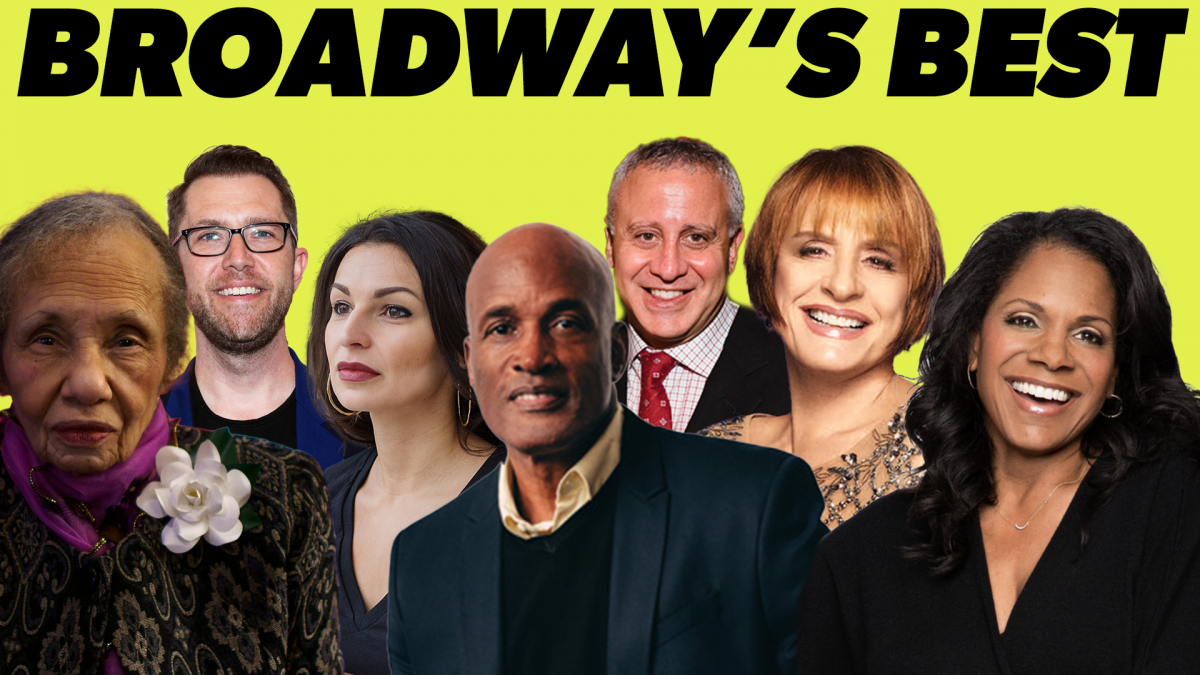

Pictures From Home—a new American play based on the late Larry Sultan’s photo memoir of the same name—celebrates both its Broadway bow and world premiere on Thursday, February 9th. Now playing at the landmark Studio 54, Pictures From Home vividly brings to life a heartfelt, tragicomic portrait of a family, all captured through the lens of a son’s camera.

As the play dares to ask, “How do you capture a lifetime?” Well, we know you don’t have all day, so here is just a snapshot of the incredible and inventive work of the stars of Pictures From Home.

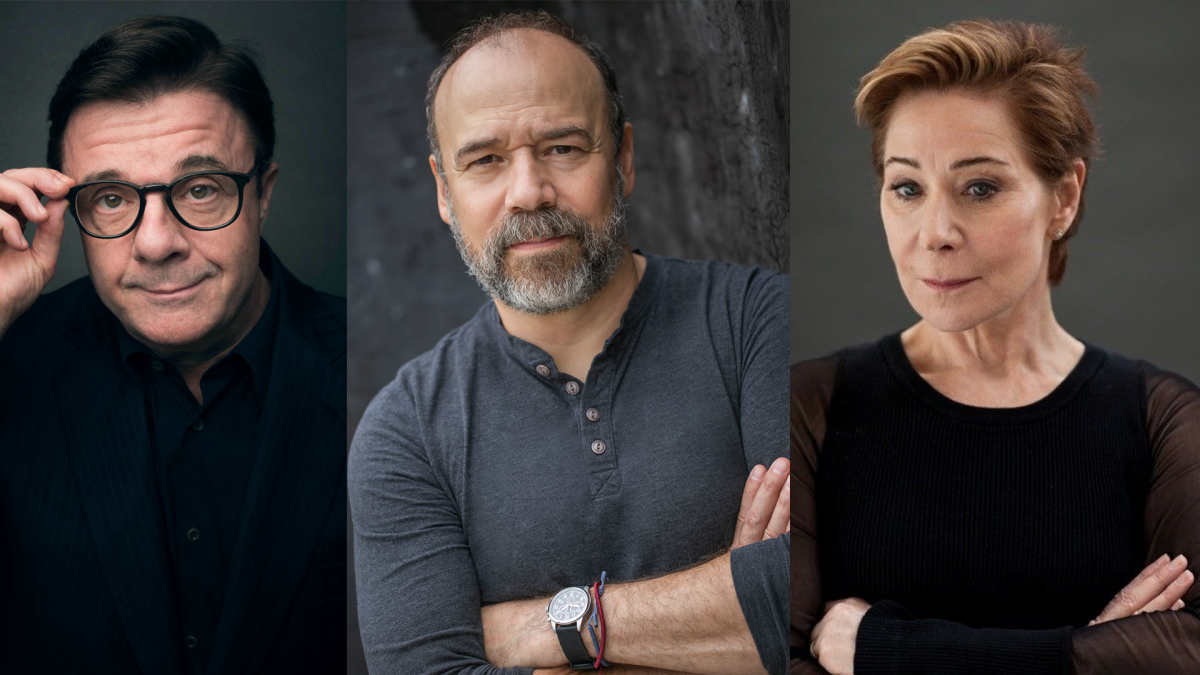

Nathan Lane

With a heavily-lauded career that has spanned stage, television, and film, Nathan Lane has become a household name. Currently playing Irving in Pictures From Home, Lane was last seen on Broadway in 2019 playing the titular character in Gary: A Sequel to Titus Adronicus. And prior to that, Lane deftly portrayed Roy M. Cohn in the Royal National Theatre’s Broadway transfer of Angels in America, which earned him his third Tony Award (the other two being for 2001’s The Producers and 1996’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum). But on a night indoors, turn on the TV and catch Lane as the indomitable Ward McAllister in HBO’s The Gilded Age (Season 2 coming soon) or as Ted Dimas in Hulu’s Only Murders in the Building (for which he won the 2022 Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series).

Danny Burstein

There’s zero argument about it: Danny Burstein is SPECTACULAR. Before assuming the role of Larry in Pictures From Home, Burstein dazzled as the boisterous Harold Zidler in the long-running Moulin Rouge! The Musical, assuring audiences that they, too, could “Can Can Can”! And that’s just what Burstein Did Did Did eight times a week, earning himself the IRNE Award for Best Supporting Actor in a Musical, the Drama League Award for Distinguished Performance, the Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding Featured Actor in a Musical, the Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Musical, and, last but not least, a Grammy Award nomination for Best Musical Theater Album.

Zoë Wanamaker

After 17 years, Zoë Wanamaker makes her long-awaited return to the Broadway stage as Jean in Pictures From Home. But since her Tony-nominated performance as Bessie Berger in the 2006 Broadway production of Awake and Sing!, Wanamaker has been no stranger to the UK theater scene. Having taken the stage with many of London’s most premier and acclaimed theater companies—including The Young Vic, Bridge Theatre, Donmar Warehouse, Royal

National Theatre, and Royal Shakespeare Theatre—Wanamaker has earned an impressive nine Olivier Award nominations, with two wins for 1998’s Electra and 1979’s Once in a Lifetime. But we’d be remiss if we didn’t also mention Wanamaker’s unforgettable work across pop culture fandoms, including her portrayals of Madam Hooch in 2001’s Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the evil villain Lady Cassandra in 2005’s Doctor Who, and Baghra in 2021’s Netflix adaptation of Shadow and Bone.

Sharr White

Pictures From Home marks the third Broadway play for playwright Sharr White in only a decade. His two other plays—The Other Place (starring Laurie Metcalf) and The Snow Geese (starring Mary-Louise Parker and Danny Burstein)—both took their bow at Manhattan Theatre Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre in 2013. But White knows his way around Off-Broadway just as well. In 2014, his two-hander Annapurna premiered at The New Group, starring everyone’s favorite real-life couple, Nick Offerman and Megan Mullally. And after that, The True, another play premiered with The New Group in 2018, starred Edie Falco and Michael McKean. And as if that hasn’t kept White busy enough, his television career boasts a number of notable credits, including writing for Showtime’s The Affair, creating Netflix’s Halston, co-showrunning HBO Max’s Generation, and writing/executive producing Apple TV’s upcoming Mrs. American Pie.

Bartlett Sher

If you’ve ever been within shouting distance of Lincoln Center, you’ve heard his name. Bartlett Sher captains the dynamic, powerhouse team of Pictures From Home as their director at helm. With a Broadway career that has spanned nearly two decades, Sher’s direction has become as

iconic as many of the theatrical titles he’s worked on. This includes, but certainly is not limited to, 2005’s The Light in the Piazza, 2008’s South Pacific, 2015’s The King and I, and 2018’s My Fair Lady and To Kill a Mockingbird. The 9 Tony Award nominations behind his name (including a win for Best Direction of a Musical for South Pacific) agree: there’s no such thing as too much Sher. And good news, there’s more! Sher’s revival of Camelot will open at Lincoln Center Theater in April 2023, AND, recently announced, Sher is set to direct the Broadway adaptation of the six-time Oscar-winning movie La La Land, with a premiere date yet to be revealed.