In one way or another, being the American president means having a relationship with the American theatre. That might mean being a regular attendee (like Bill Clinton) or a one-time Broadway producer (like Donald Trump). It might mean meeting the future First Lady while starring with her in a community theatre production (like Richard Nixon), or it might mean, of course, losing your life at Ford’s Theatre.

But more than anything, being the president means having the symbolic power of your office — and very often the specifics of your own administration — embodied on stage. As we approach another election, it’s a good time to survey how dramatists have imagined the Commander-in-Chief, because no matter who wins in November, he’ll likely find himself in a play soon enough.

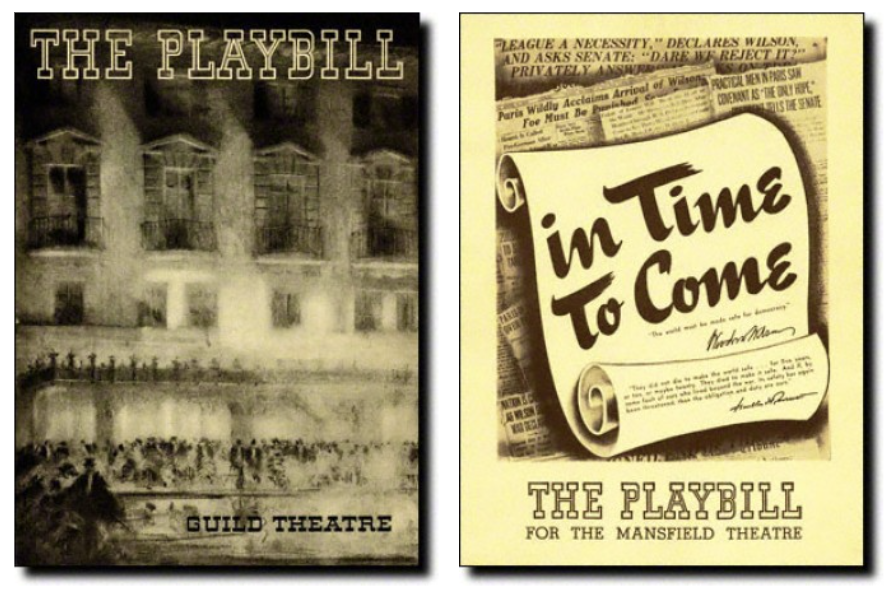

Broadway has been delivering shows about presidents for almost as long as it has existed. Take Benjamin Chapin’s drama Lincoln, which premiered in 1906 and was revived in 1909. it launched a decades-long trend of serious-minded plays that depict real-life presidents as heroes. This includes Maxwell Anderson’s 1934 drama Valley Forge, which lionizes George Washington; Charles Nirdlinger’s 1911 play First Lady in the Land, which celebrates both James and Dolly Madison; and In Time To Come, a tribute to Wilson’s creation of the League of Nations that was written in late 1941 by Howard Koch and the legendary filmmaker John Huston as a direct response to World War II.

Chapin, meanwhile, was just the first of many playwrights to respectfully depict Honest Abe. John Drinkwater had a smash hit in 1919 when his play Abraham Lincoln ran on Broadway for almost six months, and The Rivalry, Norman Corwin’s 1959 dramatization of the Lincoln-Douglas debates had a starry L.A. revival as recently as 2008, with David Strathairn as Lincoln and Paul Giamatti as Douglas. And Robert Sherwood nearly outshone them all with Abe Lincoln In Illinois, which focuses on the future president’s rise to political prominence. It opened to raves in 1938, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1939, and ran for over 470 performances.

However, it’s hard to imagine a show like Abe Lincoln in Illinois being embraced today. As historian Bruce Altschuler says in his book Acting Presidents, “Which presidents are portrayed and in what ways [tells] us quite a bit about how Americans have perceived their leaders,” and since the late 1960s, the theatre has reflected the nation’s political strife, disillusionment, and ambivalence. While the occasional play like Give ’em Hell Harry (about Truman) or musical like 1776 still depicts the nation’s leaders as the undeniable good guys, the president is now more likely to represent conflict, confusion, or downright villainy.

Just look at what happened to Lincoln: He appears in the musical Hair, which is synonymous with the counterculture rebellion, after a character’s acid trip leads to historical hallucinations. In both 1993’s The America Play and 2001’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Topdog/Underdog, Suzan-Lori Parks probes the country’s fraught racial history by depicting a Black character who performs as a Lincoln impersonator.

These more subversive productions are part of a lineage that arguably starts with MacBird!, a 1967 satire that reimagines MacBeth as the story of Lyndon Johnson’s rise to power, complete with the murder of a king who resembles JFK. At the time, this was considered so scandalous that Walter Kerr called the play “tasteless and irresponsible”, and according to Altschuler’s research, there were cries of treason at a backer’s audition. While there had certainly been shows that mocked the foolishness of American politics (including the Gershwin’s musicals Of Thee I Sing! and Let ‘Em Eat Cake), MacBird! marked the first time a major production took specific, vitriolic aim at a sitting president.

Audiences didn’t mind. The show ran for 386 performances Off Broadway and earned Stacey Keach an Obie for his lead performance. Soon enough, both sitting presidents and living ex-presidents were considered fair game.

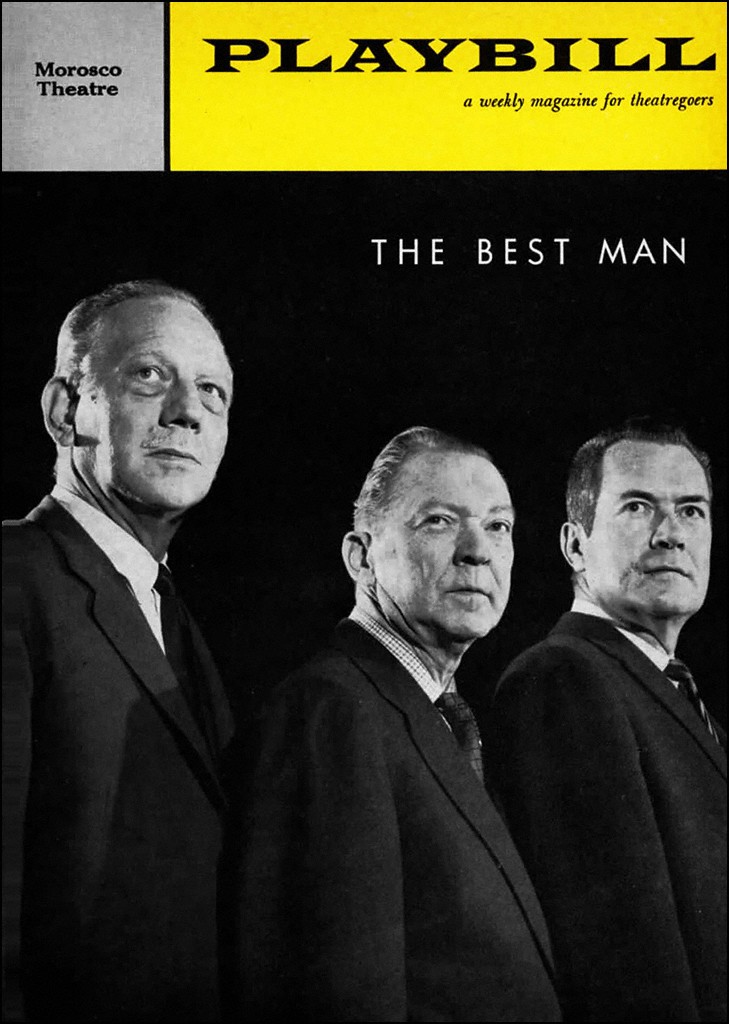

Gore Vidal is another key figure in this evolution. His 1960 play The Best Man is arguably one of the best American dramas ever written about politics, and though it draws inspiration from real-life figures like Truman and Kennedy, it uses fictional characters to probe the American political system.

Meanwhile, in 1972 Vidal wrote An Evening With Richard Nixon and…, using the then-current president’s own words in a play that sees him judged by the ghosts of presidents past. Similarly, George W. Bush was still in office when David Hare dissected his administration in the play Stuff Happens, and shortly after he left the White House in 2009, he was lampooned by Will Ferrell in the Tony Award-nominated solo show You’re Welcome America. More recently, Lucas Hnath’s play Hillary and Clinton, which came to Broadway in 2019, imagined the fateful night in 2008 when Hillary Clinton lost the Democratic nomination to Barack Obama.

With its poetic look at the Clintons’ inner lives, Hnath’s play belongs to a 21st-century tradition of presidential plays and musicals that seek to challenge our conventional understanding of a political narrative. In Michael Friedman and Alex Timbers’ Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, which premiered on Broadway in 2010, the controversial president is reimagined as an emo rock star whose volatile emotions help him gain the public’s ardor. Peter Morgan’s play Frost/Nixon shows us Richard Nixon after his resignation, when he’s lost his influence and is desperately trying to rehabilitate his reputation. And Hamilton, of course, is famous for casting the Founding Fathers with actors of color, which among other things underscores that every American deserves to take ownership of the ideals pursued by presidents like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

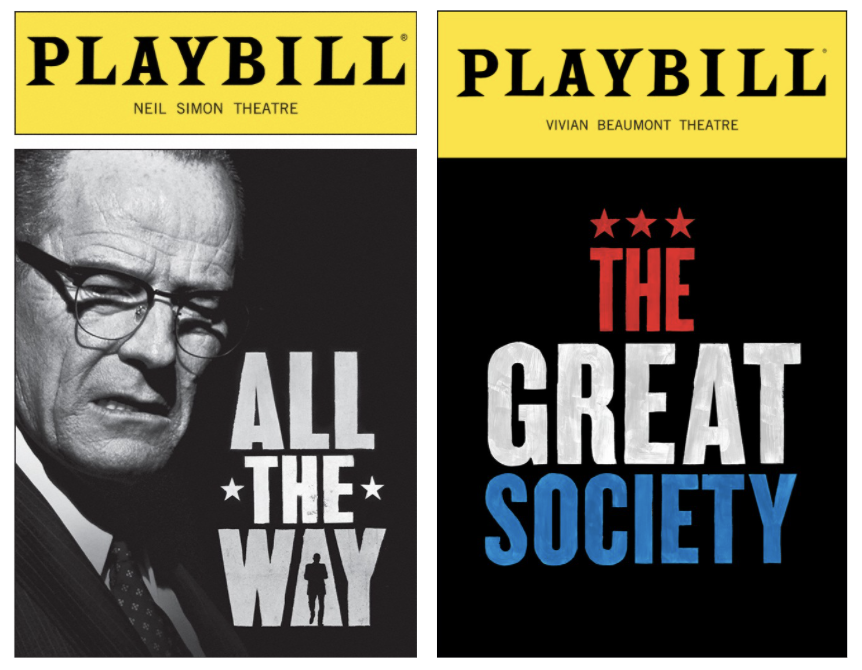

And not unlike MacBird!, Robert Schenkkan’s plays All the Way and The Great Society give LBJ’s presidency a Shakespearean tinge. Instead of satire, however, Schenkkan opts for the sweep of a history play and the emotional punch of a tragedy. All The Way, which won the Tony Award for Best Play in 2014, charts one of Johnson’s greatest victories — the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act — but this climax becomes painfully bittersweet when it’s considered alongside The Great Society, which depicts the Johnson administration’s disastrous descent into the Vietnam War.

Often, the most enduring shows about presidents — either real or fictional — stay with us because they seem to understand our current moment. For instance, David Mamet’s play November, about a fictional (and morally dubious) chief executive named Charles “Chucky” Smith, premiered on Broadway in 2008. One of Smith’s final lines (“I always felt I’d do something memorable — I just assumed it’d be getting impeached”) was funny at the time, but it feels shockingly prescient in the Trump era. Likewise, unless politicians suddenly change, the mudslinging campaign tactics in Gore Vidal’s The Best Man are guaranteed to be freshly relevant every four years.

And with this year’s presidential election feeling especially fraught, there’s no doubt it will inspire another crop of plays to keep the president on stage for years to come.

Mark Blankenship is the founder and editor of The Flashpaper and the host of The Showtune Countdown on iHeartRadio Broadway.