Launched in 2021, the 1/52 Project is a nonprofit that raises funds from theater designers, asking them to donate just one week’s worth of royalties a year, and then distributes the funds to early career designers from marginalized backgrounds. Below, the program’s creator, Tony-winning set designer Beowulf Boritt, and projection designer Stephania Bulbarella, who received a grant in 2021 and made her Broadway debut in fall 2023 on Jaja’s African Hair Braiding, discuss the necessity of the project, the forces that make life precarious for young theater designers, and their creative processes.

This Q&A has been edited for concision and clarity.

Broadway’s Best Shows

I would love to just start by asking, why is the 1/52 Project necessary?

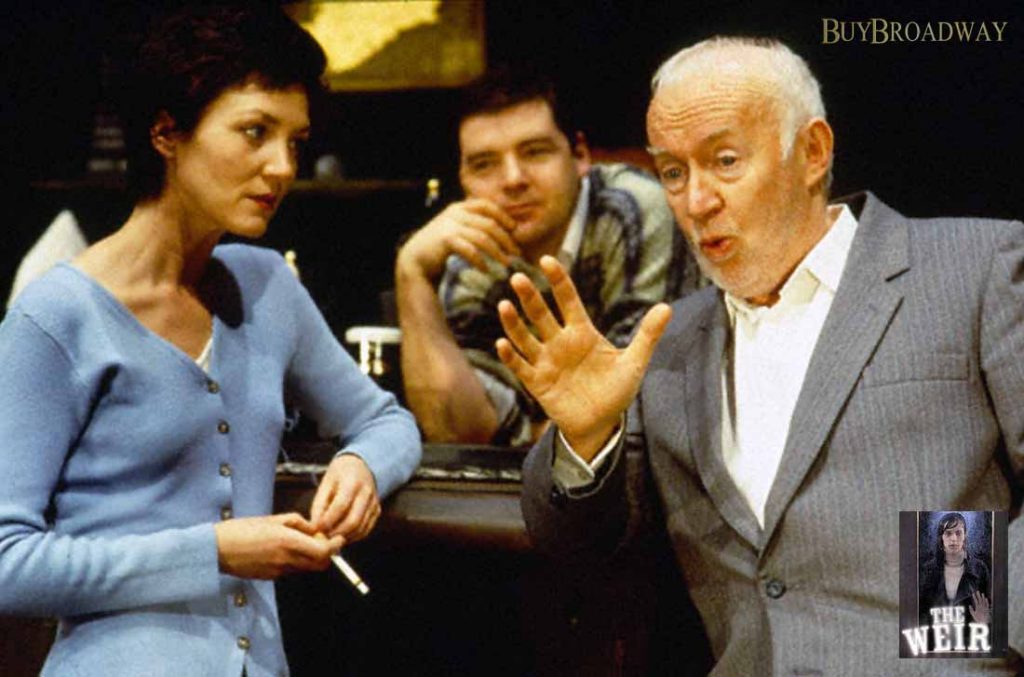

Beowulf Boritt

My quick answer is, I don’t think anyone is owed a career in the theater, but it shouldn’t be harder to have a career in the theater because you’re a woman or because you’re not white. And it is apparent and true that both of those things make it harder. My slightly longer answer is that my father came here as a refugee from Hungary in 1956, with no money at all, and got to live out the American dream. And by the time my brothers and I came along, he was able to provide a decent middle-class living for us. And it just feels, to me, that that should be possible for everybody.

Stephania Bulbarella

As an emerging projections and video designer– before the grant, I was living month to month, meaning I did not have any savings at the end of the year, or the end of the month. It felt like there were moments where I could not breathe. And then suddenly, this grant gave me the possibility of having savings, for the first time in my life I could be comfortable. I could pay my rent. That felt really incredible and safe.

At the same time, I would get some associate designer gigs, and the associate fee would be much more than a design fee for an Off Broadway show. So [with the grant] I could take on more design gigs, and be the [lead] designer.

Another key element, thanks to the grant, there were two celebrations each year, a little ceremony for giving the grant, where an incredible group of designers that I had always admired were all in the same room. It was all about presenting myself and saying hi. And it’s two years since I’ve gotten the grant and I’ve built some relationships with some of the most incredible designers in this world. Which if it was not for the grant, maybe I would have met them eventually, I don’t know, but it would have taken much more time.

BB

It was not in my head when we started doing this, but the networking part of it is valuable. our business is all about networking. Initially, I wasn’t even going to do a ceremony like that. I didn’t, I hate the fundraising! But the first year we were doing it, and it was the end of year “hooray, I got the grant!” [moment,] the rest of the committee was like no, we have to do it. We have to do it. You have to raise some money to do it. Thank god Hudson Scenic Studios agreed to just sponsor the whole thing. They just paid for the party, they have for the past two years, and they’ve already offered to again this year. It’s the generosity of the community. Neil Mazzella, [CEO of Hudson Scenic Studios], specifically saying, ‘I will pay for this thing.’ And it allows us to have a party at the West Bank Cafe, and invite everybody who contributed and get everybody into a room together.

BBS

Absolutely! It’s all about the schmoozing. Is it different being an emerging designer in 2024, as opposed to when you were starting out, Beowulf?

BB

I think it’s harder now. Because when I started out in the 1990s, there was a lot of money in the city and it meant there was a lot more small theater, [so] I got my start doing a lot of really small plays that didn’t pay very much. There were so many opportunities that I could cobble together a living doing them. It was hard work and a lot of hours, but there were more options.

I feel like –and I might be wrong about this– there are not hundreds of options for early career designers right now. And the pay gap [between assistant jobs and lead designer jobs] that Stephanie mentioned has always been true. But if you want to build a career as a designer, you have to take the [lead] design gigs.

BBS

It can be surprising to learn that being an assistant on a Broadway show actually pays more than being the lead designer of a show in a smaller theater. Building off of that, how is the path of a designer different from paths people might know, like being an auditioning actor?

BB

Part of it is, as designers, we’re responsible for big chunks of money. And if we screw it up, we’re wasting a lot of money. I think that is part of the fear of hiring people who you don’t know yet. But the result of that is it makes people likely to go back to the tried and true people and not give someone else a chance. I can sort of see both sides of the equation– a lighting designer said to me, that shows are less likely to take a chance on a set designer in particular, because on a Broadway show, I’m responsible for $1.5 million, $2 million of the budget. And if it’s not done properly, it starts taking too long [to build], and that’s also a huge part of the budget. At the same time, it also is the thing that can block people who haven’t had the chance to prove they can do it yet. And it’s that part of the pipeline issue we’re unsure how to solve.

BBS

Stephania, congratulations on making your Broadway debut, on Jaja’s African Hair Braiding! What surprised you about the Broadway experience?

SB

Well, it’s funny, but –it’s not that it feels easier. But, I’m very used to working in the Off Broadway world where the budget and crew is limited. On Broadway, suddenly there was a huge team! For example, if the system breaks on an Off Broadway show, there might be an engineer, but there might not be an engineer, and then who’s the engineer? Me. But on [Jaja], the TVs would stop working, and I would not do anything! There was a whole team to fix [it]! So in that sense, it did feel a little bit easier.

BBS

We have both a really exciting set designer and a really exciting projection and video designer here on the zoom call. I’m not saying it’s Sharks versus Jets, but I think it’s a really cool opportunity to talk about how these two different disciplines can work together. I’m curious what you think of the– not the tension between projections versus sets, but how you see them working together as technology changes and as Broadway changes.

BB

I mean, I think there honestly is a tension between them, or there can be. Almost every show I do I end up, at the end, apologizing to the projection designer because I’ve been so heavy handed with them, because I have a lot of opinions. It’s a tricky line. In general, I’m the one who’s hired first, so I’ve probably put something out there that the projection designer is then becoming a part of. And, if I’m doing a set that has a big projection element, I’ve probably conceived the set that way. Honestly, I will draw into my scenic sketches what [my] projection ideas are. Then, someone like Stefania, the projection designer, comes on board, and suddenly is faced with that. I try not to ever say, like, ‘this is what I want you to do.’ There’s no point in that because you want the collaboration! The projection designer should bring themselves and their ideas to it.

When it works well, it’s the most wonderful collaboration. My take on good collaboration is when the end result is something that neither I nor the projection designer nor the director would have come up with on their own. That’s the magic of theater and theater design. But getting there can be tricky and can lead to some hurt feelings and lots of opinions. We’re all in this because we’re passionate about it. We all have strong feelings about it. I’m very curious to hear Stephania’s take.

SB

The director will first meet with a set designer. And what I try to ask is that once I get onboarded into a project is, can I be present on those meetings? Because I really want to listen to where it starts, because after all, then we’re going to be projecting over that set or integrating video into that set. It feels really important to get involved from the beginning.

BBS

Beowulf, you’ve created this program to, as you’ve said, reduce the barriers to becoming a theater designer. Besides supporting the 1/52 Project financially, what are other actions that you would hope the design community could take in making the theater world–but particularly the highest levels, on Broadway– more welcoming to people who aren’t white, people who aren’t men?

BB

Well, it’s a big question. I don’t know if I have an answer for it. Broadway seems to have become a little more aware that this is an issue, morally, that it shouldn’t just be a white man’s club. The diversity that is appearing on Broadway right now, I hope it lasts. One of the reasons I started [the project] is I feel like the theater in general has a slightly shorter attention span. We’re always chasing the new shiny object. For about a year and a half we were all [working on getting] more women on Broadway. And then after George Floyd, we switched to, we have to get more BIPOC people on Broadway. And the thing before seems to get forgotten. And it doesn’t mean that the thing before is not still an issue! That’s why I keep pushing that this is about historically excluded groups. It’s women, and it is people of color. [The goal] is to diversify and strengthen the Broadway community and I genuinely believe that the broader the perspectives, the more interesting our storytelling goes.

BBS

I’m curious if there is some aspect of design that you want to challenge yourself with, or what project you’d love to do next.

SB

I don’t have a specific one, but one dream is doing a big Broadway musical. One that has lots of video from beginning to end.

BB

I mean, I’ve been, like, stupidly lucky in my career. So a lot of my, kind of ‘bucket list’ things I’ve already gotten to do…I do want to do Guys and Dolls on Broadway, and I want to do West Side Story on Broadway. I’ve done pieces of West Side Story, in multiple compilation shows: Prince of Broadway had a West Side Story section, Sondheim on Sondheim had a West Side Story section, Jerome Robbins: Something to Dance About had a West Side Story section.

BBS

Oh my god, let Beowulf do a complete West Side Story!