“When she’s around him, her mind dilates.” That’s how Adam Rapp describes Bella, the college literary professor in his play The Sound Inside who develops a life-changing connection with a student named Christopher. In the show, which opened on Broadway last fall, the pair’s banter about novels and academia evolves into a spiritual bond so intense that during the shocking final moments, they reveal the deepest parts of themselves.

“It’s kind of metaphysical,” Rapp says. “He walks into her world and wants to throw himself into the fire of great art, and she’s inspired by him, because she’s lost that passion. There’s an element of her seeing who she was and him seeing who he wants to be.”

Crucially, Bella and Christopher don’t see anyone else, at least not on stage. The Sound Inside was one of the season’s most notable two-handers (or play for two actors), a form that has proven to be one of the most resilient in modern theatre.

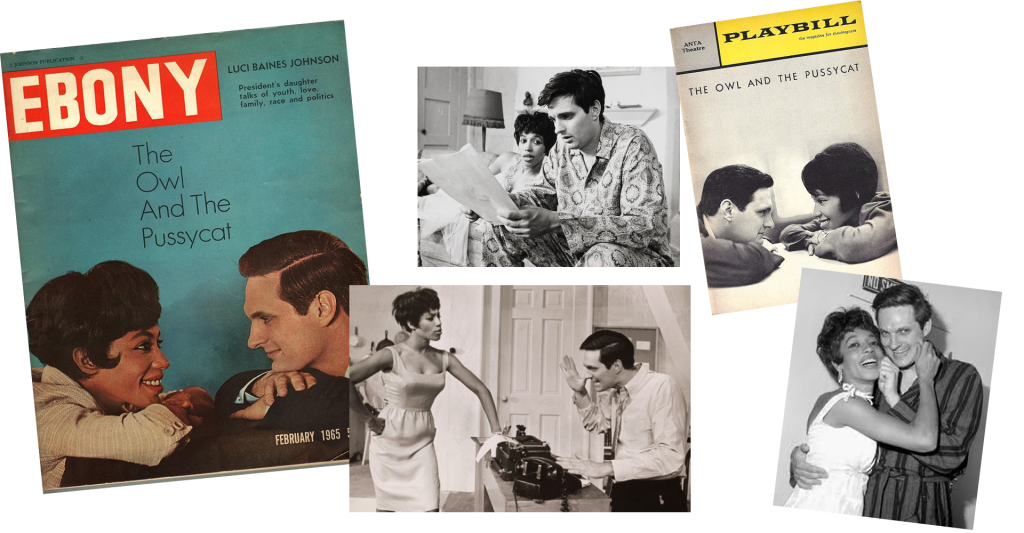

On Broadway alone, two-handers like The Fourposter and Red have won the Tony Award for Best Play, while Talley’s Folley and Topdog/Underdog earned the Pulitzer Prize in the midst of their runs. Two-handers also led to Tony Award-winning, breakout roles for Anne Bancroft (Two for the Seesaw) and Nina Arianda (Venus in Fur) and earned Tony nominations for Ruth Wilson (Constellations) and Diana Sands (in a production of The Owl and the Pussycat that famously broke the color barrier in 1964).

And that doesn’t even account for two-hander musicals. I Do! I Do!, adapted from The Fourposter, is arguably the most notable example on Broadway, running for over 500 performances in the 1960s. And titles like The Last Five Years, John and Jen, Goblin Market, and Murder for Two have made two-person tuners part of the Off-Broadway landscape for decades.

But why? What is it about this type of show that’s so appealing?

Sometimes it’s a practical choice. “When I was coming up, a lot of playwrights would talk about things like unit sets and small casts, because you’d be more likely to be produced,” says Rapp. “It was more cost efficient.” He wrote Blackbird, his first two-hander, after downtown theatre troupe Mabou Mines gave him a grant to experiment with directing his own work. Company founder Lee Breuer encouraged him to cut his teeth on something straightforward, so he wrote a play about a troubled couple trying to survive in a dank apartment.

What started as professional prudence, however, led Rapp to some deeper reasons a two-hander can work.

“It forces you to ask really in-depth questions about the characters,” he says. “You have to keep finding reasons for them to stay together. And those questions — ‘Who’s in love with who?’, ‘Who wants to hurt whom?’ — feel more feral because two people are stuck in a room together.”

Lauren Gunderson says the form crackles with energy, and she should know. Her two-handers like I and You and The Half-Life of Marie Curie have helped her become America’s most produced living playwright. (That’s according to the record-keepers at TCG, who note that despite not having a Broadway credit, she has had an incredible number of regional productions in the last few years.) Speaking of two-handers, she says, “When you only have two people, then you know that something is going to happen between them. You can’t think, ‘Well, I don’t know. Who’s the story about?’ It can only be about these people, so for us in the audience, part of the excitement comes from wondering where we’re going with them.”

As an actor, Mary-Louise Parker has experienced that excitement firsthand. Her two-hander credits include the Broadway productions of The Sound Inside (with co-star Will Hochman) and Simon Stephens’ play Heisenberg (with co-star Denis Arndt). She says both created an unparalleled sense of urgency. “It’s risky because you’re so dependent on that other person,” she explains. “It’s like life. If you’re stuck somewhere with one other person, it’s risky, but it’s wonderful because it forces you to create a real closeness. And when it’s working, the audience feels that, too.”

Many two-handers are potent because of how they wield the dynamic between the people on stage. In Edward Albee’s A Zoo Story and Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman, for instance, seemingly banal interactions in public places escalate to horrific violence. In ‘night Mother (another Pulitzer Prize winner), Marsha Norman exploits our assumption that a woman can’t be serious when she enters the play and tells her mother she’s going to kill herself.

Sometimes, a two-hander pulls us out of reality altogether. Take Charles Ludlam’s The Mystery of Irma Vep, in which two actors play eight characters in a camp satire about monsters run amok on a posh estate. “That play lets the audience enjoy the impossibility of what they’re seeing,” says Catherine Sheehy, Resident Dramaturg of Yale Repertory Theatre. It would be much less satisfying with eight actors, she notes, because that wouldn’t let us savor how the performers (and the playwright) create so many people with so few bodies.

“There’s tension and conflict just in the act of performing it. And it turns theatrical tradition on its head, because it refuses to let us associate one body with one character.”

That underscores how challenging a two-hander can be for the actors. “I have never had another job that called on me to do as much as that one did,” says Jeff Blumenkrantz, who played a collection of suspects in Murder for Two during its extended Off-Broadway run in 2013 and 2014. “The challenge really hit me in rehearsal. I was on stage the whole time, so for the entire eight-hour rehearsal day, I was required to fire on all cylinders. It was exhausting, but it was also really rewarding. Whatever was happening on stage, I knew for a fact that I was contributing to it.”

For Parker, the primary effort comes in staying connected with her co-star. “You have to keep the energy between two people really taut,” she says. “It’s like somebody at the top of a mountain dangling a rope: You can’t let go. I think of it being that intense.”

While performing in The Sound Inside, she was especially fascinated by the interplay between Bella’s monologues to the audience and her intense scenes with Christopher, who never addresses anyone but her. “There were some moments when I actually felt like I was in two places at once,” she recalls. “I was with him and with [the audience], talking to them. I was still working on that quite actively when the play ended, and I would just die to get the chance to do it again.”

And there it is again: The reminder that two-handers, these seemingly small theatrical jewels, can feel enormous. Just like a relationship with another person, the best ones can create an intimacy that dilates our minds.

Mark Blankenship is the founder and editor of The Flashpaper and the host of The Showtune Countdown on iHeartRadio Broadway.