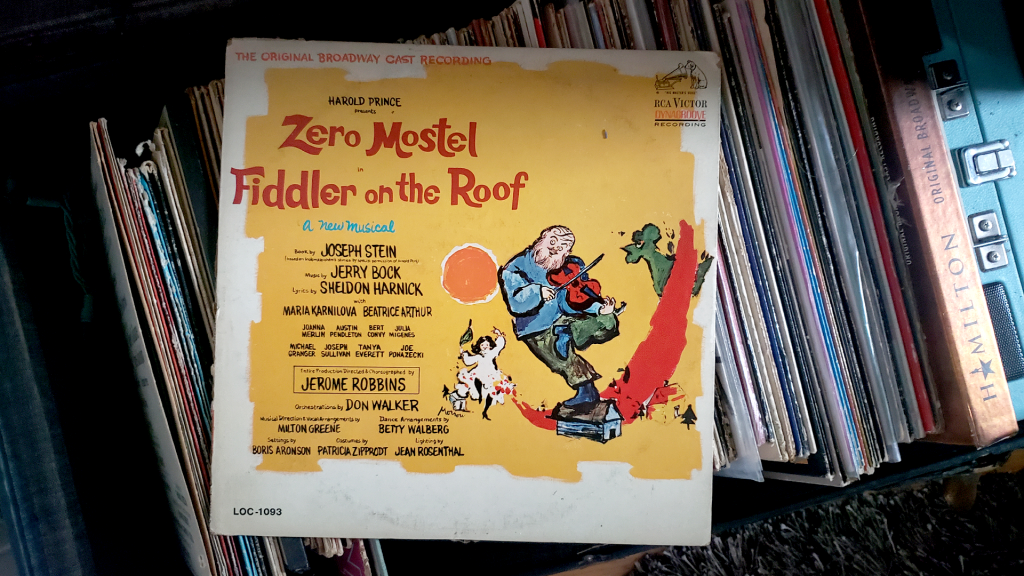

If it’s been a while since you dusted off your collection of classic Broadway albums, there’s nothing like a nostalgia-packed listening session to transport you to a simpler time. Hearing golden-piped leading ladies warble full-throated anthems while you attempt Jerome Robbins choreography in the privacy of your living room is a guaranteed fun evening!

And to make it even more festive, we’ve paired wines and cocktails with some of our favorite classic Broadway scores.

West Side Story

Based on Romeo and Juliet, with music by Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, West Side Story is undoubtedly one of the most thrilling scores in Broadway history. The star crossed love story is set against the teenage gang wars of New York City. The music covers multiple genres, from the Latin rhythms “America” and “The Dance At The Gym” to the beatnik jazz touches of “Jet Song” and “Cool” to the swooning romantic ballads “One Hand, One Heart” and “Somewhere,” which have become standards. Our hero, Tony, is the son of Polish-American immigrants, and his love, Maria, is Puerto Rican. So, we suggest you make yourself two cocktails (it’s a long show after all)…

For Tony, pick up a bottle of Polish vodka. Belvedere, created from Polish Dankowskie Rye and quadruple-distilled, is an excellent choice when combined with ginger beer and elderflower in a Polish Mule. More adventurous palates should try Zubrowka, a traditional Polish bison grass flavored vodka that dates back to the 16th century and is delicious in a Grapefruit Thyme cocktail.

For Maria, choose a Puerto Rican rum. Don Q is the top-selling rum in Puerto Rico, and many locals claim it’s the best. Keep it classic with a Daiquiri or Pina Colada, or use an aged rum to make an unexpected take on an old-fashioned.

The Music Man

The tale of a charismatic con man selling fake hopes and empty promises to naive citizens of small-town America might hit a little too close to home at the moment… but if you have fond memories of glory days in your high school marching band, Meredith Wilson’s sunny, melodic score is an instant mood-lifter.

Full of rousing marches (“76 Trombones”), upbeat ditties (“The Wells Fargo Wagon”), and romantic ballads (“Til There Was You”), this appealing musical comedy is a nostalgic treasure featuring classic Americana touches such as an Independence Day celebration and even a barbershop quartet. The climactic scene where our leading man is unmasked as a fraud occurs at River’s City’s annual ice cream social. In that spirit, our listening party pairing for The Music Man is a grown-up, boozy ice cream float! Try a Boozy Cherry Vanilla Float spiked with vanilla vodka, a Whiskey Root Beer Float, a Blackberry Gin Fizz Float, or a Chocolate Stout Brownie Sundae Float.

Guys and Dolls

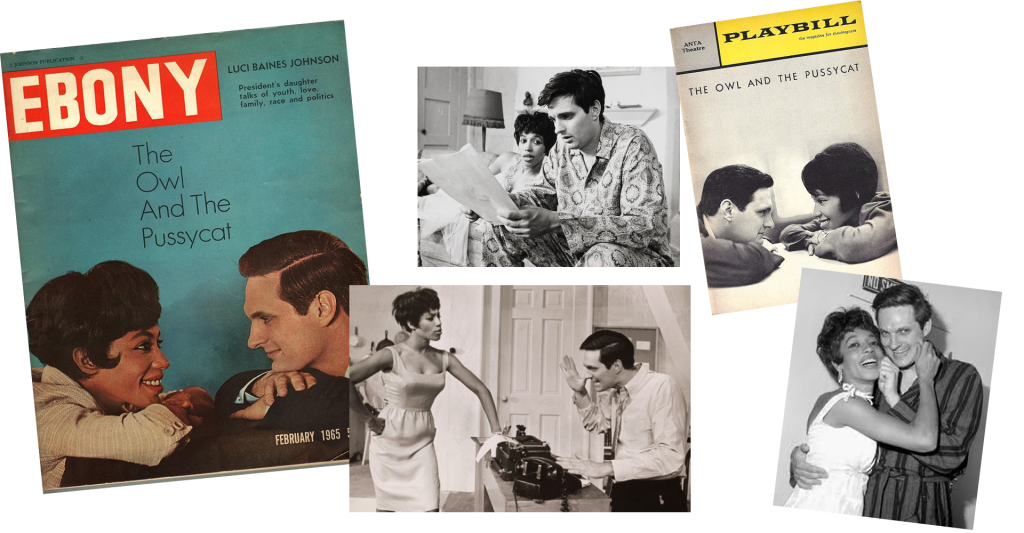

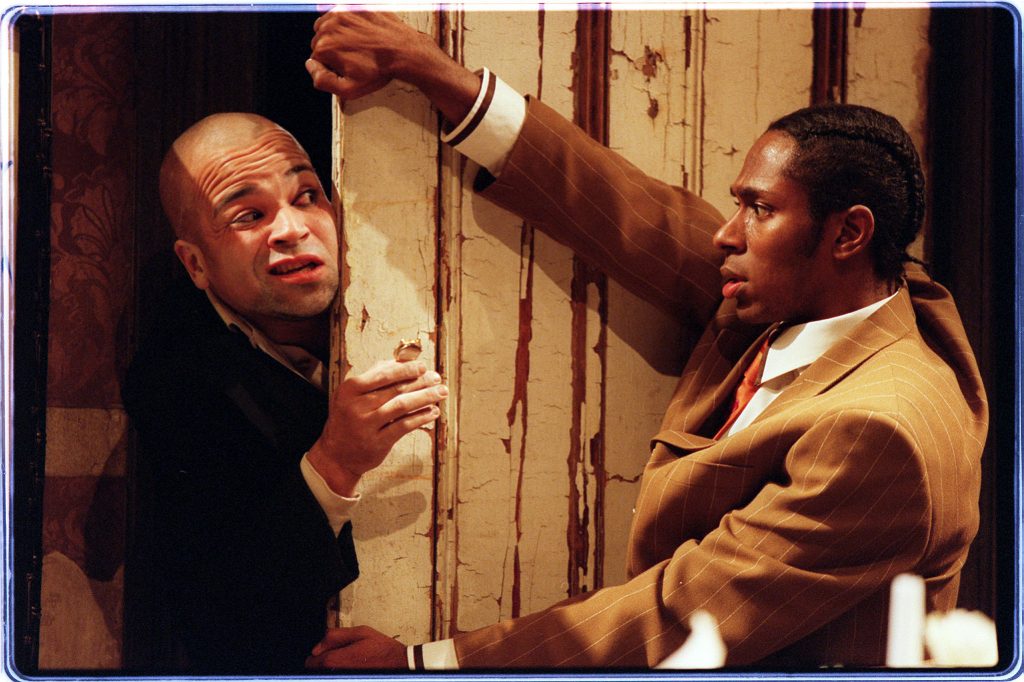

A musical adaptation of Damon Runyan’s short stories about Manhattan’s underworld in the mid-20th century, Guys and Dolls is chock full of colorful, whimsical tunes by Frank Loesser where gangsters, gamblers, nightclub performers, and other quirky characters all converge. When Gangster Nathan Detroit bets gambler Sky Masterson $1000 that he can’t get prim, proper, teetotaling Sergeant Sarah Brown of the Save-a-Soul Mission to join him for a night in Havana, hi-jinks ensue. Standout hits from the cast album include “Luck Be a Lady”, “I’ve Never Been in Love Before”, and “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ the Boat”.

The booziest moment in the show comes during the Havana escapade when the pious Sarah attempts to order a milkshake– and Sky asks the waiter to bring a Bacardi rum cocktail called ‘Dulce de Leche.’ This prompts one of the funniest lines in the show as Sarah becomes more intoxicated and exclaims: “You know, this would be a wonderful way to get children to drink milk!” Efforts to find a Dulce de Leche recipe in cocktail books from the 1950s came up dry– so it’s likely that the playwright was referring to a creamy Cuban rum drink, the Batido. However, in 2009 Bacardi created a new Dulce de Leche cocktail recipe in honor of the Broadway production that year; get the recipe here and shake one up!

And of course– if you’re suffering from a bad, bad cold after being engaged for 14 years, you could always forego the rum milkshake and go straight to one of these cold remedy cocktails instead.

Hello, Dolly!

The tale of Dolly Gallagher Levi, a professional busybody/matchmaker, has been a hit since Thornton Wilder’s 1938 play. It became a musical with music and lyrics by Jerry Herman in 1963, with a legendary leading performance from Carol Channing– and gained further immortality for the film version starring Barbra Streisand. And the most iconic scene is Dolly’s big return to the Harmonia Gardens restaurant in the title number when we see waiters rushing around the opulent dining room with Champagne buckets, floral arrangements, and crisp linens before Dolly’s entrance down that grand staircase.

For a beverage pairing as decadent as the scene, pop a bottle of Champagne! True Champagne is only made in the Champagne region of France, and it’s made with the utmost attention to care and craft… so it can command a premium price tag, but some things are #expensivebutworthit, and Champagne is absolutely one of those things! For an elegant brut style, try Besserat de Bellefon Bleu Brut, perfectly balanced between citrus, apricot, and praline tones. For something clean, lean, sleek, and mineral, grab a bottle of Ruinart Brut Blanc de Blancs. And rosé fans, Laurent-Perrier Cuvee Rose won’t disappoint with tangy and bright layers of fresh red cherry and raspberry flavors.

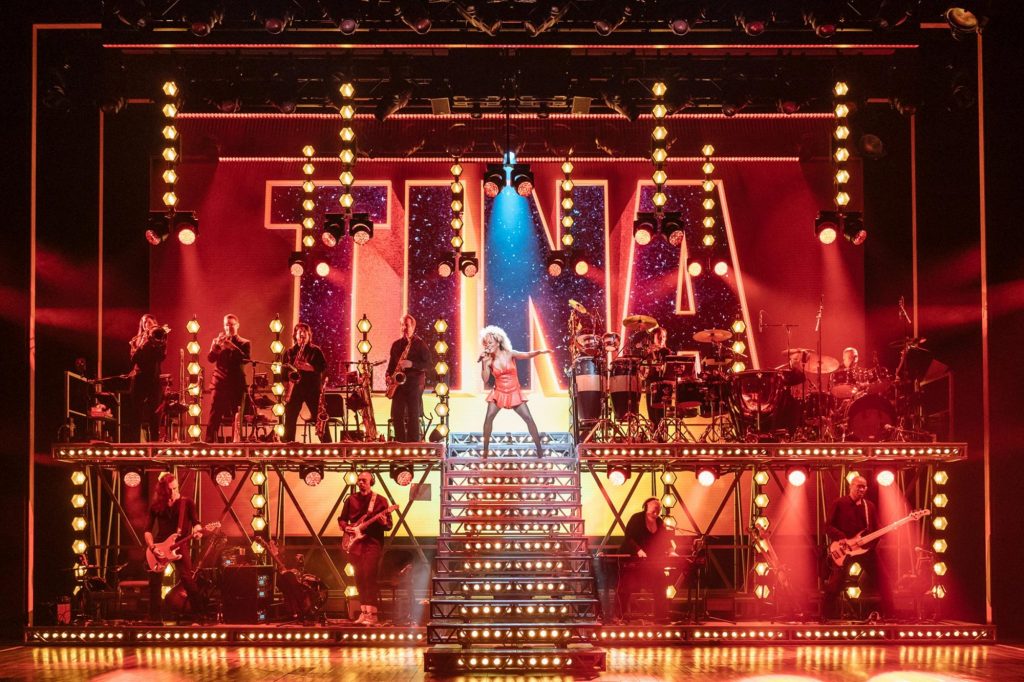

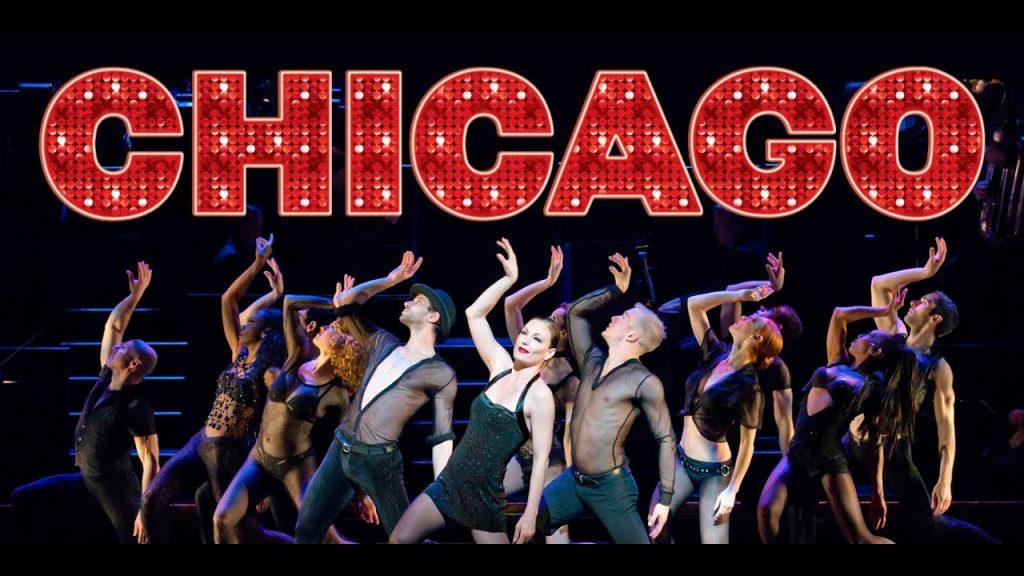

Chicago

Set in the jazz age of the roaring ’20s, Chicago is a dark and stylish peek into the lives of Vaudeville chorus girls and ‘merry murderesses’ with music by John Kander and lyrics by Fred Ebb. The plot is based on actual events of a series of high-profile cases in Chicago when attractive young women killed their husbands or lovers and got acquitted. The show is just as legendary for its concept and choreography by Bob Fosse as it is for memorable songs like “All That Jazz”, “Cell Block Tango”, and “Razzle Dazzle.”

The cast album (the original and the 1997 revival are both excellent) immediately transports listeners to a sexy spot where the gin is cold… so elevate your listening experience by mixing up a Prohibition-era cocktail! There are much better gin options nowadays than Matron Mama Morton was likely brewing in her bathtub… so grab a bottle and mix up a Gin Rickey, a Bees Knees, or a Last Word. We’re partial to the Southside— a mix of gin, mint, lemon and simple syrup– which allegedly got its name from some 1920’s gangsters on the South Side of Chicago who created this cocktail to make their homemade gin more drinkable! A perfect pairing for a sultry night in.

Sarah Tracey is a certified sommelier, entertaining expert, and wine educator based in New York City. Whether teaching classes, creating custom beverage programming for corporate and media events, or exploring wine regions world-wide, she’s driven by her love for producers who make fabulous wines and are also mindful of our environment. With years of experience, knowledge, and a certification from the Court of Master Sommeliers, above all, Sarah is a fierce believer that wine should always be approachable, festive, and fun.

Follow Sarah Tracey on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and on her website for more wine and cocktail tips and tricks!