By Harry Haun

‘Even though I know how to write a play, I want a novella in the theatre.’ I was excited by that. You couldn’t put the story down. It was so evocative. It was like diving into a beautiful novel.

Because director David Cromer more or less specializes in drama—much more than less but not exclusively—he was surprised to get his 2018 Tony for a musical. Granted, “The Band’s Visit” was a character-rich musical and he fortified it with three Tony-winning performances from the cast (Tony Shalhoub, Katrina Lenk and Ari’el Stachel), the turf was still unfamiliar to him. It was to be Hal Prince’s last show, and, when he couldn’t make it, its producers scouted around for a likely replacement, their sites finally settling on Cromer because of the care and craft he showed drama.

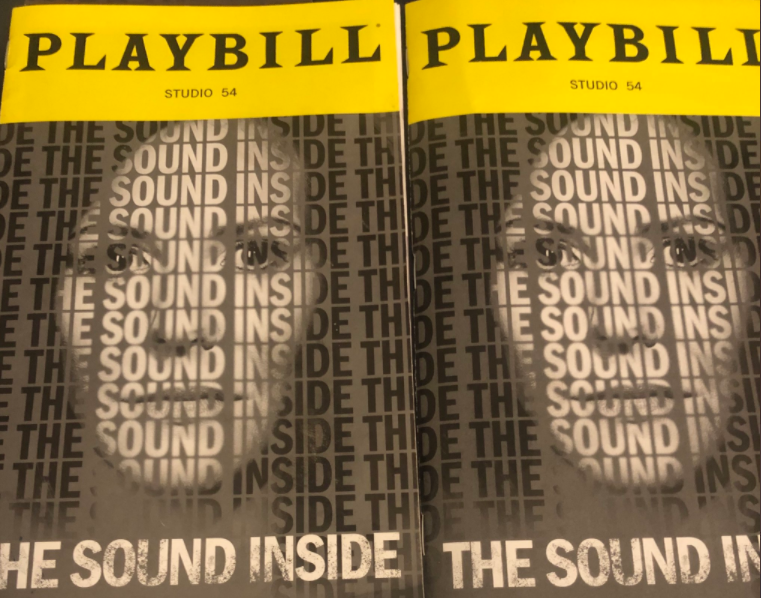

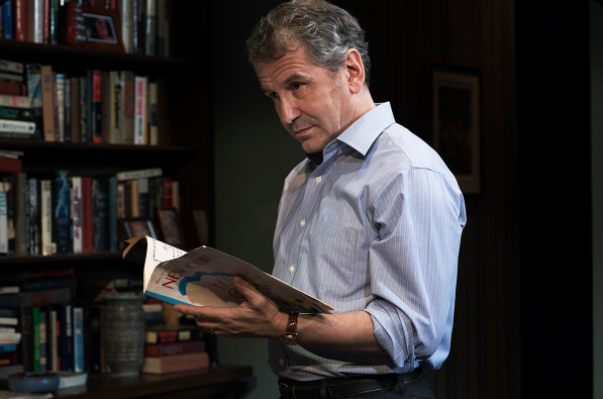

Currently, Cromer is contending for his second Tony more comfortably with something right down his alley. “The Sound Inside” is a play that theatrically pushes the envelope.

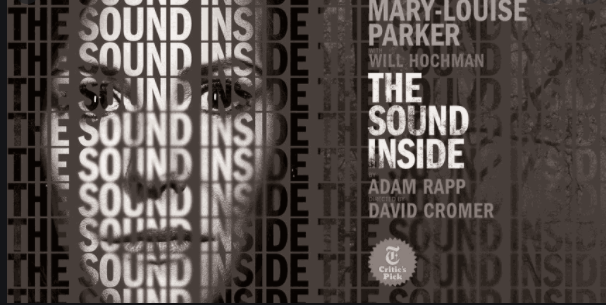

Its author is the prolific Adam Rapp. Like Cromer, he is a Chicago native who started his invasion of New York’s theatre scene in 2000 by transplanting his Steppenwolf productions Off-Broadway. In 21 years, he has turned out 26 plays, one of which (“Red Light Winter”) was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2006. “The Sound Inside” marks his first time on Broadway and his first shot at a Tony.

“I’ve known Adam forever, in Chicago and here,” Cromer says. “We actually have the same agent. When this play came up, I was given it to read. Usually if I get a new play, I procrastinate, fearing the worst. This, I whip through in one sitting and said yes.”

At first glance, the director found much to admire about the piece. “It was just so rich. I love that it challenged the theatre form. Adam is a very gifted playwright who wrote a play which he was aggressively turning back into prose. He said, ‘Even though I know how to write a play, I want a novella in the theatre.’ I was excited by that. You couldn’t put the story down. It was so evocative. It was like diving into a beautiful novel.

“I was drawn to trying to explore the feeling of reading prose by yourself, reading a great novel on a cold night, with only one light on, at home—but in the communal experience.”

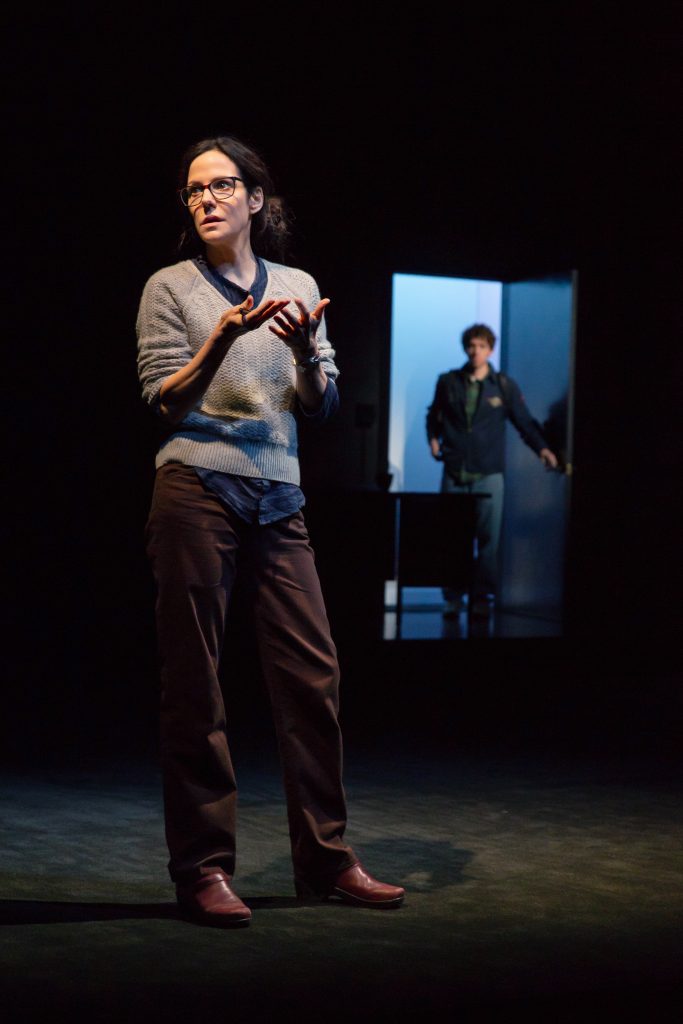

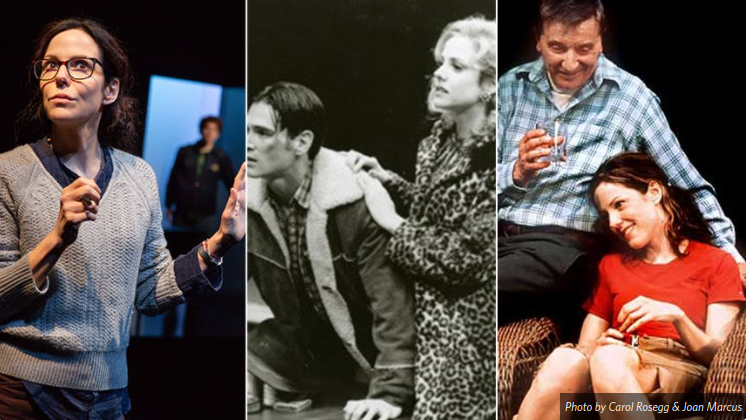

“The Sound Inside” had its shakedown-cruise premiere in June of 2018 at Mandy Greenfield’s Williamstown Theatre Festival and opened on Broadway in October of 2019 at Studio 54. Mary-Louise Parker, who’s performance is Tony-nominated, carries a star’s load of the show alone, playing a seriously ill Yale creative-writer professor who narrates the play verbally but constantly scribbles in her notebook as if she’s writing the story she’s living. A Broadway-bowing Will Hochman plays the only other character in the play, a wannabe young writer she takes under her wing to mentor, hoping he can come to her aid.

Parker, one of our most articulate and persuasive actresses, was already attached to the project when Cromer came aboard. “I don’t know what Adam was thinking when he wrote it, but he may have done what he always does, which is to write and then he finds an actor later,” figures Cromer. “Mandy and Adam and Mary-Louise had already decided that they wanted to do that play at Williamstown, and I was the last piece of the puzzle and I think she and I were a good team. I would love to take credit for that performance, but I can’t. She’s one of the best there is.

The amount of memory work Parker’s part requires was pretty staggering. “It was, I’m sure, very difficult for her to do. It was a problem because it also kept changing. It evolved. Mary-Louise has great instinct about the progress of a play, and Adam was doing beautiful work rewriting while we rehearsed. It was hard, and we all just kept making it harder—but to the betterment of the play.”

“Mary-Louise must manifest so much of it and not have anything but her voice to do it. She was alone a lot of the time. We were happy when Will came on, but she had to spend most of it alone.”

Hochman was a find the director is particularly proud of. “Will was the last guy who came in. He heard about the play, got to read it and really hustled. He came in and said—not literally, of course—‘No one will work harder on this than me. No one will give you everything they’ve got like me.’ So that was exciting. When he left the room, Mary-Louise said ‘Yup, that’s the one.’

“What’s interesting about Will is that he wanted to be an actor all his life, and he wouldn’t admit it. He went to college and studied finance, and finally, late in college—it was like coming out of the closet—he said, ‘Goddammit, I want to be an actor.’ And, a couple of years later, he’s starring in this play on Broadway. He had not spent his life preparing to do it, and then, through grit and determination, got it there. You hope The Guy is going to come in and appear. You hope you can solve this terrible problem, which is we don’t have anyone for the play. He came in and won it.”

The drama at hand comes at you in a kind of theatrical freefall where you’re offered a variety of interpretations, not the least of which is that the whole story might have happened in the head of Parker’s character. Cromer believes it’s a matter of sorting out what’s real and what’s not.

“Mary-Louise’s character wrote a piece about a kid who ran through a wall. She called the kid Billy Baird, and her name is Bella Baird. In the play she tells us her mother had neurofibromatosis, that terrible illness that creates tumors and becomes cancerous. Then later, when she finds out she has cancer, she doesn’t want to go through what her mother went through. She says, ‘I don’t have neurofibromatosis. I just have good old-fashioned cancer.’

“That’s what Adam’s mother died of. First of all, none of it is real. It’s all created. Bella’s a teacher at Yale, and Adam was a teacher at Yale. Every life is made up of a bunch of little details. It’s all constructed out of other things. Everything we look at is made out of other things. It’s all real, it’s all happening, and then none of it is happening. I change my mind about what is true in this play all the time.

“Adam lived it–so it’s all real, and, simultaneously, none of it is real–which is the pure nature of art. It can be interpreted many ways. I interpret it many ways depending on the day, and actors will interpret it different ways on different days.”

Harry Haun has covered theater and film in New York for over 40 years. His writing has appeared in outlets such as Playbill Magazine (“On the Aisle” and “Theatregoer’s Notebook”), New York Daily News (where he wrote a weekly Q&A column (“Ask Mr. Entertainment”), New York Observer, New York Sun, Broadway World and Film Journal International.