“Sometimes it seems…as though only intelligent people are stupid enough to fall in love & only stupid people are intelligent enough to let themselves be loved.” – Elizabeth Bishop, from her notebook

Dream

I see a postman everywhere

Vanishing in thin blue air,

A mammoth letter in his hand.

Postmarked from a foreign land.

The postman’s uniform is blue.

The letter is of course from you

And I’d be able to read, I hope,

My own name on the envelope

But he has trouble with this letter

Which constantly grows bigger & bigger

And over and over with a stare,

He vanishes in blue, blue air.

–Elizabeth Bishop, Uncollected Poems, Drafts and Fragments

“Elizabeth told me about Robert Lowell. She said, “He’s my best friend.” When I met him a few years later, I mentioned that I knew her and he said, “Oh, she’s my best friend.” It was nice to think that she and Lowell both thought of each other in the same way” (Thom Gunn, Remembering Elizabeth Bishop, 244.)

“While we were with her, she managed to finish ‘North Haven,’ the poem [or elegy] for Lowell. She read it to us and walked about with it in her hand. I found it very moving that she felt she could hardly bear to put it down, that it was part of her. She put it beside her plate at dinner” (Ilsa Barker, Remembering Elizabeth Bishop, 344)

“I can remember Cal’s carrying Elizabeth’s “Armadillo” poem around in his wallet everywhere, not the way you’d carry the picture of a grandson, but as you’d carry something to brace you and make you sure of how a poem ought to be.” (Richard Wilbur, Remembering Elizabeth Bishop, 108)

FORWARD

The great poets Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell were great friends, and they wrote over eight hundred pages of letters to one other. When I was on bed-rest, pregnant with twins, a friend gave me their book of collected letters Words in Air: the complete correspondence between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell. I already had a long-standing obsession with Elizabeth Bishop; my obsession with Lowell and their friendship now began. I could not put the letters down. I hungered to hear them read aloud; I particularly longed to hear letter number 157 read out loud. Number 157 is Lowell’s most confessional letter to Bishop, and I think, one of the most beautiful love letters ever written. In it, he says, about not asking Bishop to marry him: “Asking you is the might have been for me, the one towering change, the other life that might have been had.”

Reading these eight hundred pages, these strands of two lives, intersecting, rarely meeting–I thought: why do I find this narrative so compelling, even though theirs is not a story in the traditional sense? I was desperate to know how the “story” would come out—how each life would progress, how the relation would end. But I also loved how the letters resisted a sense of the usual literary “story”—how instead, the letters forced us to look at life as it is lived. Not neat. Not two glorious Greek arcs meeting in the center. Instead: a dialectic between the interior poetic life and the pear-shaped, particular, sudden, ordinary life-as-it-is-lived.

Life intrudes, without warning. Elizabeth Bishop’s great love and partner Lota commits suicide without much warning. Bishop has multiple asthma attacks, and often needs to be hospitalized for alcoholism and depression. Robert Lowell dies suddenly of a heart attack in a taxi cab en route to see his ex-wife, Elizabeth Hardwick. As he died in the taxi he held a painting of his third wife, painted by her ex-husband, Lucian Freud. Lowell had bipolar disorder, and often found himself quite suddenly in a sanitarium. Bishop and Lowell’s carefully built, Platonic poetic worlds are intruded on constantly by the vagaries of life and the body. And through such sudden disturbances, their letters were like lanterns sent to one another across long distances. Bishop lived in Brazil most of her life, and Lowell lived in New York, Boston and London. Their friendship was lived largely on paper, though they met at crucial times in their lives.

Bishop was in New York when Lota commited suicide, and she stayed at Hardwick and Lowell’s apartment. They paid for her ambulance ride through Central Park, a result of a bad fall she took, perhaps induced by too much drink, after Lota’s suicide. Bishop was plagued her whole life with alcoholism; at one point a friend eliminated all the liquor in her house and Bishop was reduced to drinking rubbing alcohol and ended up in the hospital. Lowell visited Bishop in South America and was hospitalized in Argentina for a manic episode.

Their correspondence spans political epochs—coups in Brazil, the Vietnam war—personal epochs, and literary epochs. Bishop observes Lowell’s trajectory as he creates the confessional movement in poetry. I love, in the letters, the extraordinary dialectic between Lowell’s more confessional mode and Bishop’s formal restraint. Her disgust for the confessional, however, didn’t keep her from loving Lowell’s poetry. They both carried each other’s poems in their minds and in their pockets. Lowell carried Bishop’s Armadillo (a poems she dedicated to Lowell) in his wallet, a kind of talisman for how a poem ought to be.

Lowell wrote Skunk Hour for Bishop, as well as many sonnets, and a poem called “Water”, about a seminal weekend the two of them spent in Maine.

After Lowell divorced Jean Stafford in July of 1948, he visited Elizabeth Bishop in Maine. It’s a visit they would both return to again and again in their letters and in their poetry. It’s impossible to reconstruct exactly what happened; we know from letters and poems that they spent the weekend together, at one point standing waist high in water, and Bishop said to Lowell, “When you write my epitaph, you must say I was the loneliest person who ever lived.” Bishop wrote later that they were: “Swimming, or rather standing, numb to the waist in the freezing cold water, but continuing to talk. If I were to think of any Saint in his connection then it is St. Sebastian—he stood in a rocky basin of the freezing water, sloshing it over his handsome youthful body and I could almost see the arrows sticking out of him.”

We know that shortly after that visit, Lowell told some friends he was going to marry Bishop. Soon after, they had a drunken weekend at Bard where many poets were gathered. Lowell was rumored to have proposed to her that weekend. Bishop wrote to another friend, “Saturday night was worst—a really drunken party, I’m afraid, with everyone behaving very much the way poets are supposed to.” In another account, Bishop remembers that she and Elizabeth Hardwick had helped a drunken Lowell back to his room, taken off his shoes and tie, loosened his shirt, upon which Hardwick said, “Why, he’s an Adonis!” and Bishop said “from then on I knew it was all over.”

We also know from their friend Joseph Summers that at the end of the Bard weekend, “He and Elizabeth seemed to be very much in love that weekend. He was saying, ‘Now let me know when you are coming back.’ And she said, “I don’t know.’ “Let me know where you are,” and so on.” Another friend reports, “She told us at one point she loved Cal more than anybody she’d ever known, except for Lota, but that he would destroy her.” And from another friend: Lowell “was the one of the few people Bishop addressed in her poems. She said that he had proposed to her, and she had turned him down.” Apparently her greatest regret was not having a child, and she considered having one with Lowell early on, but worried about the history of mental illness in both of their families.

The gaps between their letters, the mysterious interludes in which Lowell and Bishop actually saw each other, leaves much to the imagination. Their letters are so hyper-articulate that one almost has the impression that no bits of life were lived without been written down. These silences between the letters fascinated me as much as the letters themselves. But rather than invent dialogue for these interludes in which they actually met, it felt important to me to let Bishop and Lowell speak only in their own words. Bishop’s reserve, and her insistence on not mixing fact and fiction, was always with me as I arranged the letters. All the words from the play are taken from their letters and from their poetry.

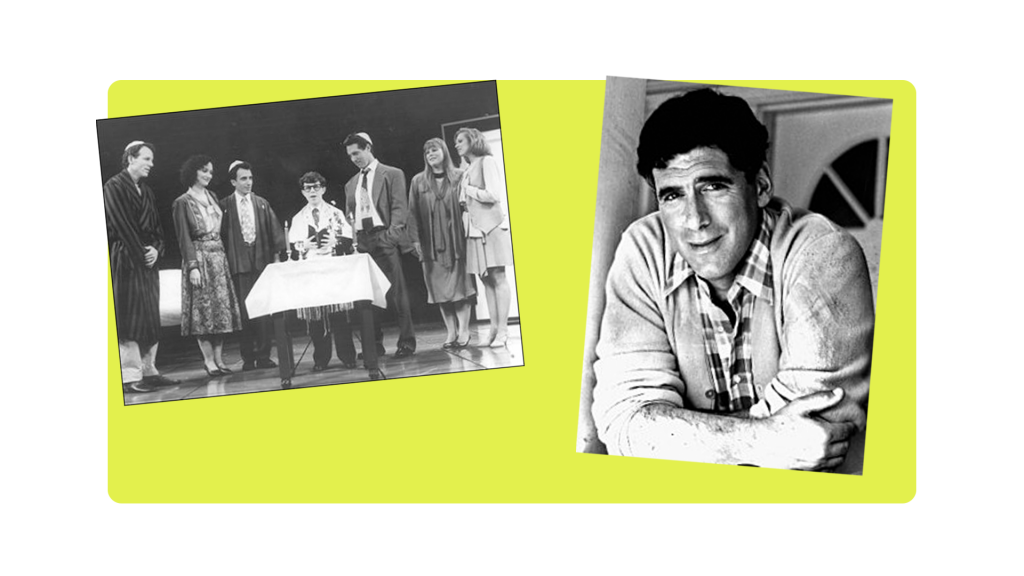

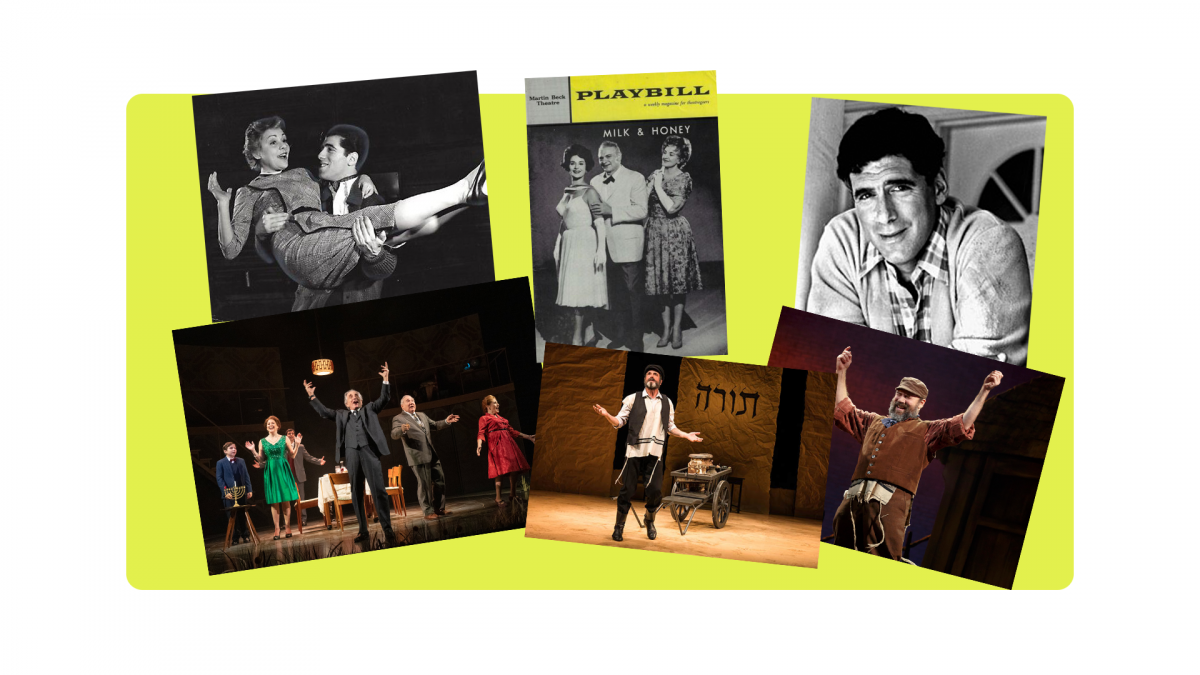

There are many ways to do this play. One can imagine the full spectacle I have suggested in the stage directions, complete with planets appearing and water rushing onto the stage, as in its premier at Yale Repertory Theater. I wanted to see the images in their letters made three- dimensional, to somehow see the reach of their imagery. But I’m also interested in how much the language can do all by itself. One can imagine, for example, a simple book club version. I saw pictures of one such event in Illinois and was very moved by the simplicity of non-actors who loved poetry reading the letters out loud to fellow travelers. One could also

imagine doing the play in a library, at a poetry foundation, or even doing the play on the set for another play on its dark Monday night. You really need nothing more than a table and two chairs for two wonderful actors who could even read the letters straight from the page rather than memorizing them. You might then use someone to read stage directions rather than projecting subtitles.

Regardless of how the play is performed, in a theater or in a room, when I first read the letters, I felt that they demanded to be read out loud, whether by actors or by lay-people. Bishop and Lowell had unerring, consummate ears, and they wrote poetry for a time when Lowell could command massive crowds in Madison Square Gardens, all gathered to hear him read his poems out loud. I offer this arrangement, then, in the spirit of a contemporary hunger to hear poetry out loud. I think we are starved for the sound of poetry. I wonder if Bishop and Lowell are among the last great people of letters to write out their lives in letter form. Their letters become almost a medieval church constructed in praise of friendship. It’s difficult to write about friendship. Our culture is inundated with the story of romantic love. We understand how romantic love begins, how it ends. We don’t understand, in neat narrative fashion, how friendship begins, how it endures. And yet life would be unbearable without friendship.

– Sarah Ruhl