It’s all but forgotten now, but The Cool World still points like an arrow at how the country was changing at the beginning of the 1960s.

By: Mark Blankenship

It’s all but forgotten now, but The Cool World still points like an arrow at how the country was changing at the beginning of the 1960s.

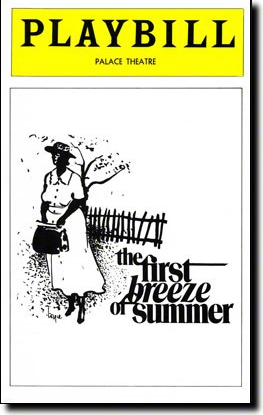

As Warren Miller was writing his 1959 novel about youth gangs in Harlem, JFK was promising voters he would deliver social change, the Civil Rights Movement was building toward its zenith, and the Vietnam War was beginning its years-long escalation. When he adapted the tale for Broadway in 1960, the American theatre was absorbing the impact of socially and politically conscious plays like Gore Vidal’s The Best Man and Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. Even a crowd-pleasing musical like Bye Bye Birdie was making audiences contend with the hero’s racist mother.

Or to put it another way, The Cool World arrived when millions of people were actively trying to understand the cracks in the social contract. Perfectly attuned to its moment, it told a story that was lifted from the the very streets the country was learning to see.

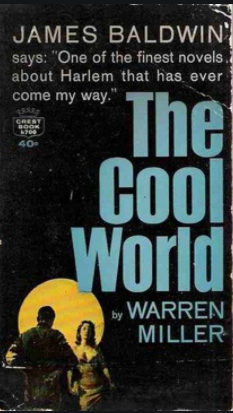

Miller wrote his novel while he lived in Harlem himself, watching young Black men participate in gang activity. His story follows Duke, a teenager determined to rise through the ranks of his crew, and it is brutally unsentimental about how violence, racism, and classism warp the boy’s life. When the book was published, Miller’s unvarnished style earned immediate praise from artists like James Baldwin, who called it “one of the finest novels about Harlem that had ever come my way.”

Robert Rossen was another fan. Well-known at the time for writing and directing the Oscar-winning film All the King’s Men, he worked with Miller to co-write the stage adaptation of The Cool World and then directed its Broadway premiere.

Granted, the production only ran for two performances, but it nevertheless gave major roles to future stalwarts like Cicely Tyson, James Earl Jones, Roscoe Lee Brown, and a 22 year-old Billy Dee Williams, who played Duke.

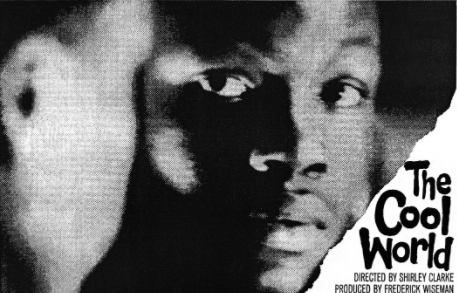

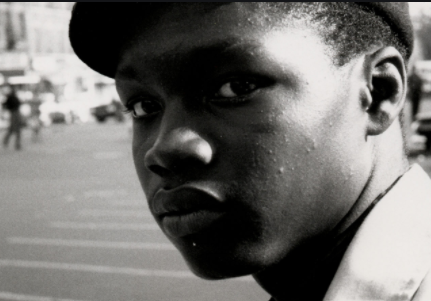

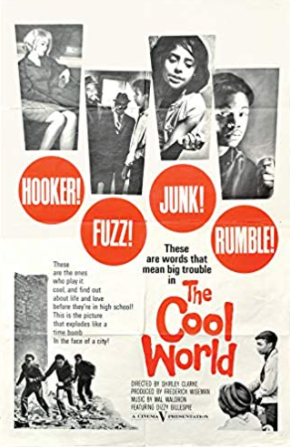

And they were hardly the last major artists to be involved with this story. In 1963, legendary documentarian Frederick Wiseman produced a film version, which was directed by Shirley Clarke, who had been Oscar nominated for a documentary of her own.

That sensibility made her film stand out: Though she worked from a script that she adapted from the novel and the play, Clarke let the movie feel like nonfiction. She cast several non-actors who lived in Harlem, and she included long, improvisatory scenes that aimed to capture the actual rhythm of the neighborhood.

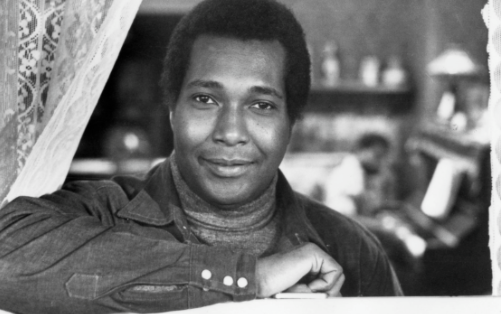

Just like the play, the movie’s cast featured future stars, including Clarence Williams III and Gloria Foster. No less than Dizzy Gillespie wrote the music, and his soundtrack album is still regarded as a classic among jazz fans.

It should be noted, of course, that The Cool World is a story about Black boys that was not created by Black people. Miller, Rossen, and Clarke were all White, and a modern audience might be understandably skeptical of their take on Harlem. Still, the novel, the play, and the film remain excellent reminders of how American culture shifted in the early 1960s and how the arts documented the change as it happened.

Mark Blankenship is the editor of The Flashpaper and the co-author of the recently published book Madonna: A to Z.