Gore’s first venture in the theatre was the result of a teleplay that had been produced on the Goodyear Playhouse in 1955; It was described thusly: “A visitor from another planet arrives on Earth and seems anxious to provoke a war- “one thing you people do really well”. The teleplay starred Cyril Ritchard, at the height of his US popularity having created the role of Captain Hook in Peter Pan. He starred as Kreton, the visitor who had hoped to cover the United States during the Civil War, and through a time warp, had arrived in the 1950’s, upending the household of a General in Manassas, Virginia. The popularity of the Playhouse presentation inspired Gore to expand the “Visit” into a full-length play and it opened to mostly positive reviews in February of 1957.

Brooks Atkinson in the Times called “Planet” “uproarious” and Life Magazine called it “the freshest and funniest invasion of the Broadway season.” Not only did Ritchard create the role, he also directed the production. The play was later adapted into a Jerry Lewis film which bore little resemblance to the original. In the fall of 2000, there was a special reading of “Visit to a Small Planet at the Douglas Fairbanks Theatre. The cast included Alan Cumming (as the Visitor), Lily Tomlin (in the gender-changed role of the General), Philip Bosco, Christine Baranski, Kristin Chenoweth and Tony Randall, directed by John Tillinger. One could have charged premium tickets. While the reading was positively received, its future was dimmed when Cumming, who was approached to continue in the role, was unable to schedule a commitment.

His most famous play would open three years later. When it opened in 1960, it was simply titled “The Best Man” and acclaimed as one of the best political plays ever on Broadway. It ran for over a year at the Morosco Theatre and the leading role won Melvyn Douglas the Tony Award for Best Actor. In the fall Douglas had portrayed President Warren G. Harding in “The Gang’s All Here” but here he was merely a former Secretary of State who was was an aspiring Presidential Candidate at a convention. The play was written pre-primary politics which has subsequently become a staple on the American scene, though that spring there would be the first highly publicized major Presidential primary with Senators Stuart Symington, Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey and John F. Kennedy vying to be the Democratic candidate. In the play the opposing candidates were famously drawn upon Adlai Stevenson who had twice been the Democratic presidential candidate and Richard Nixon. Almost stealing the spotlight was the character of the ex-President and potential kingmaker (patterned after Harry Truman) portrayed by Lee Tracy, who recreated the role in the film, which co-starred Henry Fonda and Cliff Robertson.

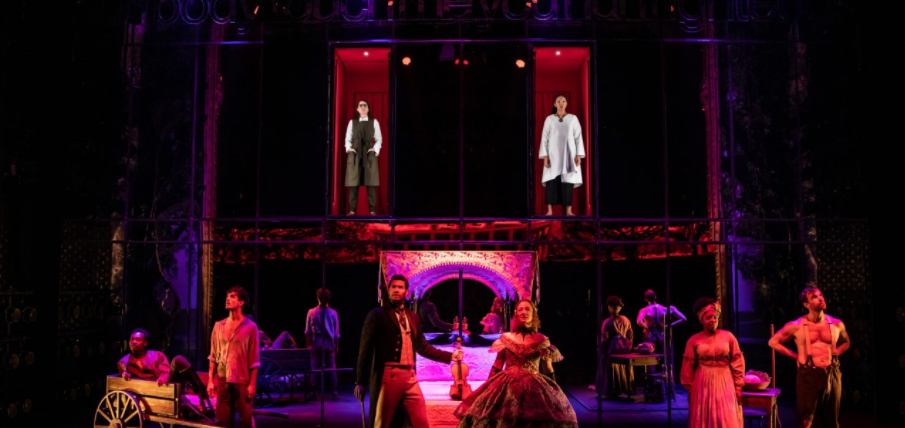

When the play was revived in the year 2000, it came on the heels of the popular film “The Best Man” which starred Taye Diggs. When the producer Jeffrey Richards, with director Ethan McSweeney, travelled to Ravello to meet with Vidal, it was suggested, to avoid confusion, that the play be retitled “Gore Vidal’s The Best Man”. Gore’s response: “I thought you’d never ask”. The production which co-starred Charles During, Spalding Gray, Chris Noth, Elizabeth Ashley, Michael Learned and Christine Ebersole won both the Drama Desk Award and the Outer Critics Circle Award for Best Revival and was a surprise success of the fall season. It also benefitted from the five week delay in the Presidential contest which resulted in the George Bush presidency. A line that before the election did not get a laugh was noted to receive one after November 4th when the putative candidate Joe Cantwell remarked “and the last thing we want is a deadlocked convention.”

There was a second revival of the play in 2012 with another all-star cast including John Larroquette, James Earl Jones, Eric McCormack, Angela Lansbury, Candice Bergen, Jefferson Mays, Kerry Butler, and Michael McKean. Again the play was a success. Gore attended the second week of rehearsals in a wheelchair and serenaded the company with stories about the original production and the night that JFK attended a performance. Unlike the first revival in which he joined the company on stage at a glittering opening night with celebrities in the audience included Woody Allen, Susan Sarandon, Tim Robbins, Bebe Neuwirth, Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick among others, Gore was unable to attend the second re-opening. He died later that year, during the engagement of the production, which focused attention on his life and work and, consequently, resulted in an extension of the play with a replacement cast of Cybill Shepherd, John Stamos, Elizabeth Ashley and Kristin Davis.

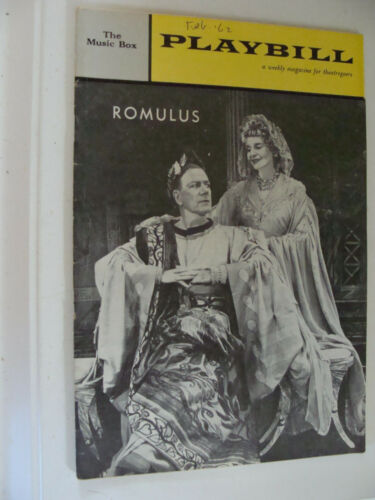

Gore’s third Broadway play was an adaptation of Frederich Durrenmatt’s “Romulus” about the last of the Roman emperors. premiered on Broadway in 1962; once again his director and star was Cyril Ritchard (Vidal quipped- “Cyril was a wonderful actor but as a director he would just tell the actors to stand there, in a line and recite the dialogue”) and Dame Cathleen Nesbitt and Howard DaSilva were also starred.

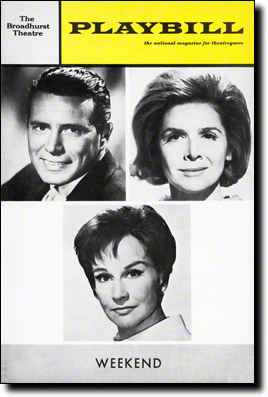

His fourth play reunited him with the original director of “Gore Vidal’s The Best Man”, Joseph Anthony, but did not repeat the success. The play was “Weekend “and a one sentence description of the play read as follows: “An unscrupulous Republican senator’s son brings home his black girlfriend”. The play opened in March of 1968; the previous December the Spencer Tracy-Katherine Hepburn-Sidney Poitier film had a similar racial theme in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” and was Oscar-nominated and a big box office success. “Weekend” was neither a box office success, despite a starry cast which included John Forsythe, Rosemary Harris and Academy Award winner Kim Hunter and introduced Carol Cole, Nat King Cole’s daughter, as the girlfriend, nor was it well received. The producers advertised it without quotes calling it THE PEOPLE’S CHOICE. It wasn’t. It played three weeks at the Broadhurst Theatre.

Gore’s fifth and final play on Broadway was in 1972; a blistering satire called “An Evening With Richard Nixon and…” with George S. Irving in the title role. Originally scheduled to be directed by (Sir) Peter Hall, it was directed by Ed Sherin, who had staged “The Great White Hope”. It opened 50 years ago and was budgeted at $150,000; there was a cast of fifteen (with a very young Susan Sarandon) portraying a gallery of over 50 characters ranging from George Washington to JFK, including, FDR, Harry Truman, Thomas E. Dewey, Dwight Eisenhower, FDR, Gloria Steinem and Pat Nixon – Clive Barnes in his review said “I laughed a great deal at this political bloodletting” but had reservations about the play’s cumulative impact. So did audiences, and without the star power that had been associated with previous Vidal entries, the play last only two weeks after opening at the Shubert Theatre.

Gore’s final play that received a production premiered at Duke as part of Duke Theatres’ Previews in 2005. A glittering cast headed by Charles During, Chris Noth, Michael Learned, Harris Yulin, Richard Easton, Isabel Keating and David Turner brought “On the March to the Sea” to life for a brief engagement. Directed by Warner Shook, who had brought “The Kentucky Cycle” to Broadway, “Sea” was a noble effort that failed to march on to New York. The play concerned a Georgian family’s trial by fire during Sherman’s famous march during the Civil War. Vidal delighted students at a writing class with various bon mots such as “The best writers have been actors…Shakespeare, Shaw, Twain, Wilder.”; “Reading is like going to bed with someone. Save Jane Eyre for a dismal night” and on the staged reading format of the play “naked language…the eye is not distracted by the adventurous and dangerous set designer”…

Gore had developed and was retooling a script inspired by his novel Lincoln (which had also been a mini-series on television in the late 80’s) when he passed away. A reading had been scheduled and ultimately was not realized.