By Katie Devin Orenstein

This year’s 76th Annual Tony Awards will be broadcast live from the United Palace in Washington Heights on Sunday, June 11th. As this year’s nominated shows head into the final stretch of their awards campaigns, Broadway’s Best Shows is here to remind you that no one is guaranteed a Tony, not even Aaron Tveit. Here is a list of our top 10 surprise upset wins, across 76 years of Tony history.

10. Christopher Ashley wins for directing Come From Away – 2017

Conventional wisdom had the category as a showdown between Michael Greif for Dear Evan Hansen and Rachel Chavkin for Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812, parallel to the competition happening over in the Best Musical category. Perhaps because Greif and Chavkin split the vote, Christopher Ashley was genuinely flabbergasted when he won his first Tony. Ashley was previously nominated in the same category for Memphis and The Rocky Horror Show.

The cast of Come From Away performs in the 2017 Tonys:

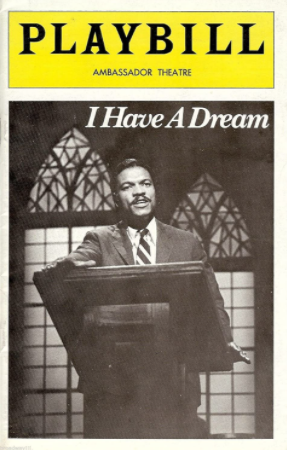

9. 1978 Best Play

The Pulitzer Prize-winning The Gin Game was the anticipated winner for best play – that, or Chapter Two, a comedy about grief from Broadway heavyweight Neil Simon. However, the Tony voters chose the lesser-known Irish playwright Hugh Leonard, for Da, a memory play about a man traveling back to the suburbs of Dublin to cope with the death of his adopted father.

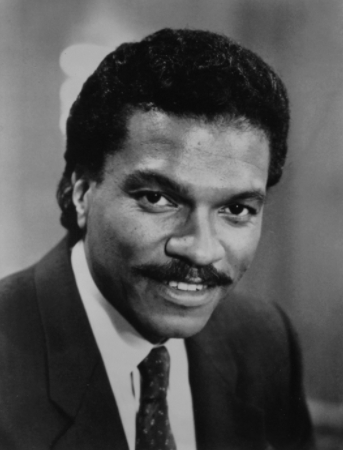

Cicely Tyson and James Earl Jones in the 2015 revival of The Gin Game:

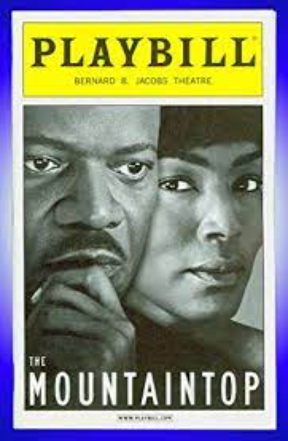

8. Follies and the 2012 Revivals category

For whatever reason, Follies has particularly bad Tonys luck, as we also discuss below. Its revival in 2011, starring Bernadette Peters, Jan Maxwell, and Elaine Paige, was not a major commercial success, but it was expected to win the Best Revival category against Evita, Jesus Christ Superstar, and Porgy & Bess. Instead, the Diane Paulus-directed Porgy won the statue.

Norm Lewis, Audra McDonald, and the company of Porgy & Bess perform at the 2012 Tonys:

The always delightful Danny Burstein performs a song from Follies at the 2012 Tonys broadcast:

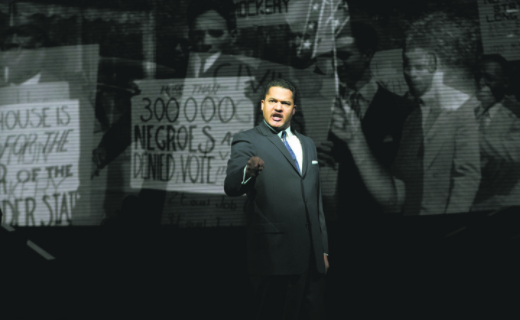

7. Children of a Lesser God wins Best Play – 1980

Best known for its 1986 film adaptation starring Marlee Matlin, Children of a Lesser God was a watershed moment for portrayals of Deaf people in theater, exploring the complex issue of Deaf schools insisting students learn to speak, instead of using ASL. Its original star Phyllis Frelich was the first Deaf person ever to win a Tony Award. It beat out Talley’s Folly, a romance by Lanford Wilson that won the Pulitzer and was expected to win, and Bent, a gut wrenching drama about queer people in Nazi concentration camps by Martin Sherman.

Children of a Lesser God was also revived on Broadway in 2018, with direction by Kenny Leon:

6. Marissa Jaret Winokur wins Best Actress

While Hairspray was expected to win Best Musical in 2003, Bernadette Peters was the favorite to win the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for her performance as Mama Rose in Gypsy. Peters had previously won for Song and Dance and Annie Get Your Gun. But it was Marissa Janet Winokur, in her Broadway principal debut as Tracy Turnblad in Hairspray, who ended up winning.

Marissa’s acceptance speech:

5. Kinky Boots wins Best Musical

Prevailing wisdom said that Matilda, like the many British mega-musicals before it, was going to sweep the 2013 Tony awards. In a battle between the lovably sassy British drag queens and the lovably sassy British schoolchildren (only in New York!), it was the American-produced Kinky Boots that won out. Why? Perhaps its surprise win at the Drama League Awards earlier that month moved the needle, or perhaps the almost entirely American Tony voter pool wanted to support one of its own. While both shows were uplifting, Kinky Boots’ pro-LGBTQ+ rights message may have resonated extra hard. (Matilda ended up just fine though – it ran for four years on Broadway, and is still open in the West End.)

4. 2007 Best Actor in a Musical

Theater fans are still arguing over whether Raúl Esparza should have won for Company over David Hyde Pierce for Curtains. Esparza gave a heart wrenching performance as Bobby in John Doyle’s stripped down reimagining of the Sondheim classic. While the rest of the cast played their own instruments throughout the show, Esparza-as-Bobby only sits down in front of a piano to accompany himself in the finale, “Being Alive.” Sondheim is notoriously tricky for pianists, and to also act and sing it at the same time is a rare feat:

But it was beloved Frasier star David Hyde Pierce who won out, for his portrayal of a sensitive and theater-obsessed police detective in Curtains. Pierce, who had put himself into musical theater bootcamp to prepare for his debut in Spamalot a few years prior, may have been helped by his reputation as the nicest person in showbusiness, and the goodwill he had amassed by choosing to come back to Broadway after winning four Emmys for Frasier. Below, DHP and the company of Curtains perform at the Tonys:

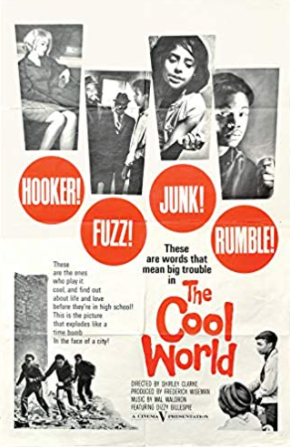

3. 1972 – Follies loses best musical

A piece of Tonys trivia that always surprises theater lovers: Stephen Sondheim’s masterpiece Follies did not win the 1972 Tony Award for Best Musical. That award went to Two Gentlemen of Verona, a groovy Shakspeare adaptation by Galt McDermot, the composer behind Hair, in collaboration with playwright John Guare. It also beat out heavyweights like Grease and Ain’t Supposed to Die A Natural Death, and Jesus Christ Superstar wasn’t even nominated in the category. There are a few theories for why this happened: first, 2 Gents is a much frothier, more optimistic show than Follies. It was a diverting entertainment that left audiences joyful, while Follies matched the dark reality of the national mood amidst the Vietnam war, Watergate, and Greatest Generation discontent. 2 Gents takes a firm antiwar stance, but it didn’t confront middle-aged Tony voters with their unhappy marriages they way Follies did. At the same time, voters may have picked 2 Gents to save face after Hair was a massive cultural moment back in 1968 but didn’t win any Tonys, making the awards seem out of touch.

2 Gents was revived off-Broadway in 2005 at the Delacorte with Norm Lewis, Oscar Isaac, Rosario Dawson, John Cariani, and Renee Elise Goldsberry. Here’s Goldsberry and Lewis performing “Night Letter” from that production:

2. Nine beats Dreamgirls

Dreamgirls was an instant, massive smash when it opened to rave reviews in December of 1981. Loosely based on the story of Diana Ross and The Supremes, and with an energetic Motown-inspired score, the production starred Jennifer Holliday and Sheryl Lee Ralph. Nine, a baroque exploration of an Italian film director’s psychosexual whirlwind based on Federico Fellini’s film 8½, had its first *workshop* performance in February of 1982, and opened on Broadway the day of the Tonys cutoff in May. Dreamgirls, directed by Michael Bennett of A Chorus Line fame, was at the Shubert-owned Imperial, and Nine played at the Nederlander-owned Rodgers right next door, and was directed by Tommy Tune. Even juicier, Bennett and Tune had once been dear friends, with Bennett having taken Tune under his wing (if you can take someone who’s 6’6” under your wing.) When Nine was quickly announced to open in the 1981-1982 season, on the final day of Tonys eligibility no less, Bennett called Tune and begged/threatened him to take the show out of town and bring it to New York next year instead. Tune refused. So the story goes, during the Tonys campaigning period in May 1982, the Dreamgirls team refused to step into restaurants the Nine people went to, and vice-versa. The American Theatre Wing, the producer of the Tony Awards, amped up the drama by seating the teams on opposite sides of the Imperial Theatre for the ceremony in June. The producers of Nine pushed their narrative as the scrappy show that could, and that Dreamgirls, backed by the mighty Shubert Organization, didn’t need – or deserve – a vote. Many in the industry were grateful for how fierce the competition got, since Broadway hadn’t had a huge hit since 1975’s A Chorus Line, and the brewing feud got lots of press. While Dreamgirls won many awards at the ceremony, including Best Actress for Jennifer Holliday, Nine shocked the world and won Best Musical. It ran for two years on Broadway, and was also revived in 2003 – when it won again, for Best Revival. Dreamgirls ran for four years, and was only briefly revived in 1987, although its historical impact as a Broadway show with three-dimensional roles for Black women and the way it tackles fatphobia, racism, and colorism in the music industry makes Nine’s womanizer-genius focus look a bit hollow in retrospect.

Jennifer Holliday brings down the house with “I Am Telling You I’m Not Going”:

The cast of Nine performs at the Tonys:

- Avenue Q bests Wicked

Stephen Schwartz’s Wicked was the enormous smash of the 2003-2004 Broadway season, its creative team and producers all established industry veterans. Avenue Q, a weirder but better-reviewed show by then-unknowns Robert Lopez, Jeff Marx, and Jeff Whitty, wasn’t expected to do well at the Tonys, or last longer than a few months on Broadway. In spring 2004, the country was also gearing up for the 2004 presidential election, and the Avenue Q producers crafted a campaign that both parodied politics and spoke to voters directly: “Vote Your Heart,” pleaded the red, white, and blue posters and buttons, and the puppets even participated in a mock debate. The producers were using a strategy first used by Nine in 1982, the last time a Best Musical race was this excruciating (see below). They appealed to the Tony voters, all 700 or so of them, to support the underdog, the subtext being that Wicked would do well regardless of whether it won, while a Best Musical win could make or break Avenue Q’s future. The campaign worked, and the little puppet show written by newcomers won not just Best Musical, but Best Book and Score of a Musical as well. Avenue Q ran on Broadway for 6 years, and Off-Broadway for another 10. Wicked seems to be doing okay too.

Note the shock on the producer’s faces when they announce that Avenue Q won: